Written by Stephen Lewis and Coco Lomas

Whatever one’s ecological and social opinions, the history of logging in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada is a fascinating story. Fortunes were made, large tracts of virgin forest were cleared and the working conditions of most loggers were horrendous. I will touch very briefly on some of these issues, but the primary focus is, as always, on a Grisdale family – a family that came to Mason County, Washington State, in the late 1890s and became significant timbermen. Bill Grisdale, one of this family, was later to be called the ‘King of the Douglas Fir Loggers’.

It’s perhaps best to start our story not in Washington but rather in the 1820s in Quebec in Lower Canada.

Logs on the River in Quebec

In the early 1800s, several English-speaking families moved from Cumberland in England to Quebec, to be more precise to Vaudreuil County, an area about 30 miles west of Montreal on the Ottawa River If any one man was responsible for inducing the Cumbrian immigrants to come to Quebec it was the Rev. Joseph Abbott. Originally from Little Strickland in the Vale of Eden, he encouraged others to follow. Between 1820 and 1837 over 50 British families had bought land in Hudson, Cote St. Charles and Cavagnal, communities in Vaudreuil, an English-speaking island in the French-speaking area. Most of them were friends and family. Though very poor it was said that they were ‘rich in hope and poor in purse’.

The first Grisdale to emigrate was Ann and her husband William Hodgson, a weaver from Matterdale who settled in Argenteuil County. The date of their arrival is not known but William died there in 1821 and was buried the same day as their 2 year old daughter Ester was baptized. Ann was now a widow with an infant, teenage daughters and a 6 year old son also named William.

Then in about 1824 Ann’s younger brother John and his wife Elizabeth Halton with their youngest son Benjamin arrived in Quebec.The Seigneur of Vaudreuil had had land surveyed and made available for settlers in the area known as Cote St. Charles. Settlers were allotted 50 arpents (approx. 45 acres) of uncleared land for about $5.00 per lot. The Grisdale siblings together occupied 3 adjacent lots there with Ann in one and John in two.

John and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth, born in Vaudreuil in June 1824. A second daughter, Hannah, was born June 1827. Both girls were baptized on 26 September 1830. When John and his wife had come to Canada they had left behind their two sons, Joseph and John, in the care of John’s parents George and Hannah Grisdale. When Hannah’s parents died in 1830, George and Hannah and the boys, by now young men, were now free to join their family in Quebec. By the autumn of 1830 the family was together again: George and Hannah, John and Elizabeth and their 5 children (Elizabeth, Hannah, Benjamin, John, and Joseph), as well as Ann Hodgson and her 5 children. Joseph and John acquired land allotments in the newly opened concession of St. Henry in Vaudreuil, not far from Cote St. Charles. Joseph’s family would remain on the farm for the next two generations.

Ninekirks, Brougham

Before we go on, let’s place this family in their Cumberland context. We might best start with George Grisdale, the ‘grandfather’, who was the oldest member of the family to go to Quebec. George Grisdale was born in 1761 in Dockray, Matterdale. He was the third child of Joseph and Ann Temple. George had married Hanna Moreland in St. Andrews Church, Penrith. Hanna’s father John Moreland and her brothers were tailors in Carlton, near Penrith. Following George and Hanna’s marriage, the family moved to the village of Brougham, east of Penrith. Since farming was George’s trade, the couple began to farm near Hannah’s parents. George Grisdale was active in Saint Ninian’s Church (‘Ninekirks’) in Brougham, and was appointed warden in 1798-1799. It was George’s two children, Ann (born 1786) and John (born 1788), who would first venture to Canada. John Grisdale married Elizabeth Halton of Dacre in 1809. Ann married William Hodgson in 1804.

It wasn’t just the particular Grisdale family of this story that decided to leave England. Many other descendants of George’s parents, Joseph and Ann Grisdale, did so as well. George’s nephew Doctor Grisdale went from the Bolton cotton mills to Pennsylvania and from there his family moved on to Oregon. Another nephew, Thomas, joined the British army, served for years in India, and ended up as a coal lumper in Melbourne, Australia. Yet another nephew, John Grisdale, emigrated to Sydney, Australia, where his family prospered. Two of George’s great nephews, John and Jonathan, also went from the Lancashire mills to Pennsylvania. Finally, another family member, also John, became a missionary and a Canadian Bishop. Quite an adventurous family!

But back to Quebec. By 1830 the Grisdale family were all together in Vaudreuil. The years passed, the 1837 rebellion came and went; ending perhaps “not with a bang, but with a whimper.” The family grew. This interesting story will have to wait till later.

Joseph Grisdale’s House – Cote St. Henri, Vaudreuil

Joseph Grisdale (1810 – 1900), the eldest son of John and Elizabeth Grisdale, was about 20 when he and his brother John emigrated to Quebec with their grandparents. He had spent time while in England getting an education as a chemist. “Being a chemist he also had a fair knowledge of the medical field and Joseph was known by many as Doctor Grisdale.” He turned to farming in his new home and acquired an allotment of 180 arpents in St. Henri, Vaudreuil. He married Mary Hodgson, daughter of Robert Hodgson and Elizabeth Kidd in 1835. They had five children: Eliza (1835) Albert Benjamin (1840), Mary Jane (1843), Elizabeth Ann (1844) and Priscilla (1847). In 1869 Albert married Elizabeth Simpson, daughter of Joseph Simpson and Caroline Grout, also immigrants from Cumberland.

Albert Benjamin Grisdale (1840-1917) and his wife Elizabeth raised a family of twelve children on their homestead in St Henry. It was some of these children who were to become the Grisdale Fir Loggers in the Pacific Northwest and who are the subject of the rest of this article. (Other children went on to great things and perhaps will be the subject of future articles). We will concentrate on some of the middle children, all born in Cote St. Charles: George Marion Grisdale (1872), John William Grisdale – called Bill – (1874), Mary Amanda Grisdale (1876), Albert Bartley Grisdale (1878) and Ralph Solomon Grisdale (1890).

There have been a lot of names already. It doesn’t matter if you remember all the connections. Yet one more name is crucial to the story; that of Solomon (‘Sol’) Grout Simpson, the uncle of the Grisdale children. The Simpsons and the Grisdales were close friends and neighbours. As forests were cut for farming, many local men had found employment cutting timber and working on the log booms along the rivers. Sol Simpson and his brothers worked as timber raftsmen, floating spruce and fir logs along the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers.

Sol Simpson

After the Civil war in America ended in 1865, Sol Simpson, a thin man with a big moustache, headed to the Nevada gold rush but found more success building railroads around Carson City. Here he won and lost two fortunes while still a young man. He married ‘Carson City’s most eligible young women’, Mary Gerrard, in 1875. When he lost his house in 1878, and was ‘practically penniless’, he moved his family to Seattle and found work driving horses for the crews that were building the settlement’s streets and railroads. Through a lot of hard work and initiative Sol gained a good reputation and some backers, which enabled him to move to Mason County where he first established S.G. Simpson Company in 1890 – which prospered by using horses to build roads and haul logs. In 1895 he founded the Simpson Logging Company in Shelton with some partners, a logging company that became not just the main local employer, but also the largest source of jobs in the whole state.

Books could be written, and indeed they have been written, about Sol Simpson’s life and the Simpson Logging Company. For our purposes the important thing to know is that George Grisdale, Sol’s nephew, had worked on the rivers just as Sol had. So it seemed natural that he would follow Sol to work in the woods in Mason County. George was 17 years old when he left Quebec in 1889 and headed for the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State. He worked hard for the next seven years, learning all aspects of the logging business. When Joe Simpson, Sol’s brother, retired from his position as Simpson’s general ‘superintendent’ of logging operations, George was appointed to take his place; a job he held until his untimely death in 1929 – to which we will return.

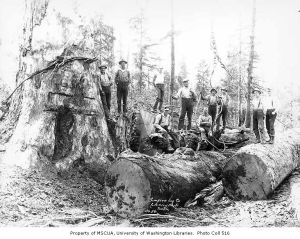

For five years after his arrival George wrote to his younger brother Bill, telling him of the wonders of the trees on the Olympic Peninsula. They were “really big and tall and thick” and he “just had to see it to believe it“. Brother Bill could stand it no longer. In 1895 he packed his bag and hopped a train heading to Washington State. By the turn of the century Bill was the foreman of Simpsons first ‘Camp One’ in Mason County. He helped Simpson to pioneer logging with teams of horses (previously done with oxen) and later working the steam donkey engines to haul the large logs up hills. Bill Grisdale replaced his uncle Robert Simpson as foreman of logging operations in 1910.

Bill and George Grisdale

Both George and Bill Grisdale raised their families in the logging camps along the railroad tracks. When children had to go into Shelton they would take the logging train, riding in the caboose. When an area was logged out the company would move the camp to another site, clearing the land, laying track and loading all of the buildings on the flatbed train to the new area. Not all of the camps had schools, so they would stay with another family in a camp that had a school.

In the beginning of logging camps, there were bunk houses that bunked about 20 men, each of whom had to provide their own mattress and bedding. Conditions in the bunkhouses depended upon the men being housed. Some refused to shower; others were neat – and clean enough to attend church. Some men chose to build their own little cabin along the tracks and avoid the rows of wet, dirty socks that often added to the aroma in the bunkhouses. There were no medical facilities. Injured loggers had to be loaded on trains to go into Shelton or, before Shelton had a hospital, taken by boat to Olympia. Best not to get injured!

Accident and death would have been witnessed on many occasions in the logging camps by George and Bill Grisdale. But they also experienced sadness even closer to home. In 1912 their younger brother Ralph decided to take a break from his studies at McDonald College in Quebec. He went to work for his brother-in-law Will Crosby in Simpson’s Camp 7. Will Crosby and his wife Mary (Grisdale) Crosby and a young son had left their home in Point Fortune, Quebec, in 1907 and moved to Mason County to work for the Simpson Logging Company. Will Crosby was hired as foreman of Simpson’s Camp 7. In February 1915, Ralph met instant death by being crushed between the drums of a big donkey engine. His gloved hand was caught in the moving cable and he was hurled into the machine. His obituary said: “He was well liked by his associates for gentle ways and clean-cut character“. George, Bill and their sister Mary Crosby must have been devastated.

Donkey Engine in Simpson’s Camp One

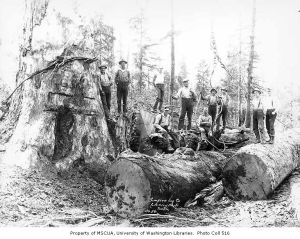

The use of ‘donkey engines’, or ‘steam donkeys’, had been something that Sol Simpson had pioneered in Washington. Donkey engine is the common nickname for a steam-powered winch. The engines “acquired their name from their origin in sailing ships, where the ‘donkey’ engine was typically a small secondary engine used to load and unload cargo and raise the larger sails with small crews, or to power pumps”.

A logging engine comprised at least one powered winch around which was wound hemp rope or (later) steel cable. They were usually fitted with a boiler, and usually equipped with skids, or sleds made from logs, to aid them during transit from one “setting” to the next. The larger steam donkeys often had a “donkey house” (a makeshift shelter for the crew) built either on the skids or as a separate structure. Usually a water tank, and sometimes a fuel oil tank, was mounted on the back of the sled. In rare cases, steam donkeys were also mounted on wheels. Later steam donkeys were built with multiple horizontally-mounted drums/spools, on which were wound heavy steel cables instead of the original rope.

A “line horse” would carry the cable out to a log in the woods. The cable would be attached, and, on signal, the steam donkey’s operator (engineer) would open the regulator, allowing the steam donkey to drag or “skid” the log towards it. The log was taken either to a mill or to a “landing” where the log would be transferred for onward shipment by rail, road or river (either loaded onto boats or floated directly in the water). Later a ‘haulback’ drum was added, where a smaller cable could be routed around the “setting” and connected to the end of the heavier “mainline” to replace the line horse… If a donkey was to be moved, one of its cables was attached to a tree, stump or other strong anchor, and the machine would drag itself overland to the next yarding location.

Simpson Loading Crew

Ralph’s death was not the only tragedy for the family. Back in 1908, married brother Albert Bartley had gone to Shelton to visit his sister Mary Crosby and to see if there was a place for him in the logging industry. While there he developed appendicitis and died. He was buried in Shelton but later his mother, Elizabeth Grisdale, went to Shelton to take his body to Hudson for burial in Cote St. Charles.

Later, in 1929, George Grisdale, the superintendant of all Simpson’s logging, and the first of the family to come to Washington, died at the age of 57. His obituary said, “George Grisdale was known as a captain of men and a friend to all.” And then two years later, in 1931, Bill Grisdale’s only son Joseph was shot to death by a crazed gunman along with five members of the shooter’s family, including two small children. Joseph Grisdale was only 25 and was the camp foreman for the Simpson Logging camp where the madman worked.

The hazards and travails of the Washington loggers’ lives weren’t just limited to unfortunate accidents or crazed gunmen. They lived for months on end in the logging camps, usually without their families, they worked a minimum of ten hours a day, they were paid a pittance and were often intimidated by the ‘Lumber Barons’ – among whom Sol Simpson and his son-in-law successor, Mark Reed, were two of the biggest. One description of a loggers’ camp describes it as follows:

Inside a bunkhouse

Loggers worked in the woods for an average 10-hour day and returned to a loggers’ camp at night, frequently in wet and muddy clothes. In the camp there was no place to wash and no place to dry wet clothes. The food was greasy and poor.

The bunkhouse was small and unventilated to the point, in the words of one investigator, “the sweaty, steamy odours … would asphyxiate the uninitiated” . The bedding crawled with bedbugs. One camp investigated found 80 men crowded into a crude barracks with no windows. The men pressed into tiny bunks and went to sleep “under groundhog conditions”. A study of logging camps made in the winter of 1917-1918 found that half had no bathing facilities, half had only crude wooden bunks, and half were infested with bedbugs. Employers blamed the loggers for the swarms of bedbugs and lice because loggers brought the pests in their filthy “bindles” or bedrolls.

A Wobblies’ Poster

It was generally thought that Simpson Logging camps were the best in the area. In 1900 a lady journalist wrote, “The cookhouse is one of the portable buildings with the storeroom overflowing with supplies. Down the length of the room run two tables with neat dark oilcloth set for 80 men. The dishes are white earthenware. The dinner is abundant and excellent…” Another journalist: “There is no better fed industrial worker on earth than the West Coast logger”

But many loggers were recent immigrants and in the years before the First World War labour was in abundant supply. The balance of power clearly lay with the employers. Unions such as the IWW (the Industrial Workers of the World) ‘tried to infiltrate the woods, sending in individuals to test the waters for organizing’. ‘This proved too be a very dangerous job’, as seen here in a letter written in 1911 by Mark Reed, Sol Simpson’s son-in-law and successor:

It is very difficult to eradicate this element entirely from our employees as they are certainly actively engaged in soliciting membership and stirring up discontent. For instance: Last week we had the misfortune to kill a man, and we had no idea until after he was dead that he was a member of this order, but found his membership card and by-laws among his effects.

Once America belatedly entered the war in 1917 things changed. The logging companies lost many key workers and the demand for spruce to supply the armed forces soared. Unrest in the camps increased and various local strikes broke out throughout the state. In July 1917 the IWW, whose members were known as ‘Wobblies’, called a timber workers’ strike. They were demanding an ‘eight-hour day, improved sanitary conditions in the logging camps, a payday to occur twice a month with a $60 a month minimum wage, the abolition of compulsory hospital deductions for non-existent services, and hiring through the IWW union hall instead of through employment “sharks,” labor agents who provided often short-lived jobs for a price to the worker’.

The lumber barons resisted fiercely. They closed down most of the logging camps. Simpson’s closed down all but one of its. This episode in American social and labour history is fascinating and many excellent studies have been written on the subject. We commend them to you; but we don’t have the space here to describe what happened in more detail. But remember that in 1917 George Grisdale was still heading all Simpson’s logging operations and his brother Bill was still in charge of the company’s Camp One. They would have been intimately involved.

The Wobblies’ strike soon ended. Mark Reed and the government’s ‘Lumber Tsar’ Colonel Brice Disque ‘both became convinced that the eight hour day should be accepted’ and negotiated a settlement and conceded an eight hour day; although some of the logging companies soon reneged on the agreement.

Returning to the Grisdale family; with the death of his three brothers, only Bill Grisdale and his sister Mary Crosby were left of the siblings who had come from Quebec to Mason County. Bill had married Esther Cornelia Callow in 1902 and besides their son, Joseph Callow Grisdale, who had been killed by the crazed gunman; they had had a daughter in 1913 called Gertrude, who was later to marry James Pauley. Older brother George had married Bertha Gouptel in 1897; they had various daughters and one son named George Marion Grisdale Junior, born in 1906, who married Frances Marian Schick and founded Grisdale Construction in Shelton. George Junior died in Shelton in 1991.

Simpson’s Camp One

Bill himself continued his work with Simpson’s until his retirement in 1947 at the age of 73. He had been with Simpson’s Logging for 49 years and in charge of Camp One from its creation until his retirement. Just before his retirement, as the towns had grown (Shelton, Elma, Matlock and Aberdeen for example) and roads were laid and cars became available, the need for moving the camp and housing the men became unnecessary. In 1946 Simpson’s built a single, modern camp. It was named Camp Grisdale, in honour of the Grisdale brothers, John William ‘Bill’ Grisdale and George Marion Grisdale. By the standards of earlier days Camp Grisdale appeared almost luxurious. People were hired to shake out sheets and clean the bunkhouses and hot showers were installed. It was one of the last resident logging camps in the nation. The closure of Camp Grisdale in 1986 ended that chapter of American history in the Northwest so often told in the folklore of Paul Bunyan.

One final note on sustainable logging: Camp Grisdale would not have been built had it not been for the Sustained Yield Contract with the US Forest Service, with the backing of Simpson boss Bill Reed. Simpson’s started its South Olympic Tree Farm in 1943; one of the first companies in the US to do so. By 1986 the company was logging in second growth stands which had had 40 years in which to mature.

Camp Grisdale

Bill’s first wife Esther had died in 1940. His second wife, Jessie A. Knight, whom he had married in 1945, predeceased him in 1954. On his retirement a dinner honouring Bill was held “which drew 200 friends and associates of the veteran timberman to Camp Grisdale cookhouse”.

Grisdale’s friends from points as far as Seattle and Portland drove 50 miles out of Shelton to the modern new camp named in honor of Bill and his late brother, George, an important figure in Simpson’s early days.

We are told that his ‘ruddy ears’ had ‘heard all the words used in logging through the past half century’. ‘But none nicer than those spoken at this party by old friends.’ His relative State Representative Arthur Callow paid tribute to Grisdale’s loyalty to his men and to his company.

All men who have worked for Bill Grisdale have respected him because he respected them.

The report continues. “The Camp Grisdale cooks spread a girdle-bursting dinner of roast turkey and Virginia baked ham, but the evening’s beans were spilled by Billy Pauley, 9 year-old grandson of Bill Grisdale.” “When called upon to give a few remarks for the family, the boy announced ‘Grandpa’s going to like that tractor an awful lot’. The tractor, a two-wheeled garden tiller purchased for Grisdale by his employers, was supposed to have been the evening’s big surprise. Billy went on ‘Oh, Grandpa had known about it for weeks.’” The tractor was called ‘Tillie’ after Sol Simpson’s wife.

Like his brother George, Bill had been an active Freemason with Mount Moriah Lodge, No. 11. On their 100th anniversary in 1964 the lodge wrote:

One of the Past Masters who now holds the record for piling up many years in one lifetime is W. Bro. J. W. Grisdale who was master in 1930. “Uncle Bill” as he is known to all of his many friends has passed his 90th birthday and is still hale and hearty. He lives in his home at Arcadia and raises a garden that would do credit to a man half his age. In summer the profusion of flowers is wondrous to behold. Bill was voted a life membership and has long passed the 50 years in Masonry mark.

In October 1965 Bill paid a last visit to Camp Grisdale. The Simpson Diamond reported: “Bill Grisdale, firm of face and frame at 91, looked around at the neat logging camp, its freshly painted buildings and neat lawns gleaming in the sun. ‘Quite a change,’ he mused. ‘It’s sure an improvement over the old ones – and we thought Simpson had the best around.’”

Bill was, says the article, “Hailed throughout the northwest as the ‘King of the Douglas Fir Loggers.’” He continued to reside at his home on Arcadia Point on the Puget Sound, 10 miles out of Shelton, until his death in 1968 at the age of 94. His time was ‘spent reading, tending a magnificent flower and vegetable garden and putting up some of the best preserves in Mason County’. No doubt with the assistance of ‘Tollie’ his two-wheeled tractor!

Bill Grisdale’s grave in Shelton

After the deaths of Bill Grisdale and his nephew George Grisdale Jnr., the Grisdale name died out in Mason County. Although there are a number of descendants of the Grisdales of Quebec, who moved to Washington State to become fir loggers, still living in the area. Coco Lomas, joint author of this article, is one. She is the granddaughter of George and Bill’s sister Mary, who married William Crosby.

All that now remains of this Matterdale name are a few fond memories and a few stories such as this one; plus a couple of enduring geographic and topographic names: such as Camp Grisdale and Grisdale Hill.

In terms of Bill, what a man, what a family! Truly one of those Paul Bunyan’s of the woods