It was probably a cold and windy day in New York’s docks in late October 1872 when two young English mothers stepped ashore. Both women had young children and they probably were holding their hands tightly as they walked down the gang-plank. Helen and Mary Ann Campbell had made the two week voyage from Liverpool on Cunard’s steamship Batavia without their husbands, Joseph and John Campbell, who had already been in America for three years. Did the women have any inkling that they would soon be in the heart of the faraway Dakota Territory and witness some of the most famous, and sad, events in the final stages of the ‘winning of the American West’? They would see General Custer depart for his expedition into the Black Hills of the Lakota Indians and the subsequent gold rush that ensued. They would be close to the last resistance of the Native Americans, their victory over General Custer and his Seventh cavalry at Little Big Horn, and the brutal massacres that followed.

Helen’s husband Joseph Hugh Campbell was a former gunner in the British Royal Marine Artillery, and a wheelwright by trade. Her sister-in-law Mary Ann was married to Joseph’s younger brother John Hugh Campbell. It’s most likely that the husbands were in New York to greet their families. Joseph would not even yet have seen his son Charles, who had been born after he had left for America. There was a third brother, Robert, who was in America too, and more than likely he came to New York’s docks too.

Great Yarmouth in the nineteenth century

All three brothers were born in the bustling maritime town of Yarmouth in Norfolk, children of millwright Hugh Campbell and his long-term partner Martha Midsummer Callf. Hugh wouldn’t be able to marry Martha until 1874 after his first wife Mary Ward had died. As the family name suggests, the Campbells were originally from Scotland, but Hugh’s grandfather, also called Hugh, had come to Yarmouth from Killin in Perthshire in about 1760. The family were always involved with the sea and some of them went off to London to build ships in the docklands of East London before returning to Norfolk. I might tell this fascinating story at a later time.

Joseph was born in 1839 and probably joined the Royal Marines in the late 1850s. We don’t know the exact date or the cirumstances. But we know that in 1861 he was serving as a gunner in the Royal Marine Artillery based at Fort Cumberland on Portsea, near Portsmouth in Hampshire on the south coast of England. Fort Cumberland was ‘first built in 1746 on the eastern tip of Portsea Island, protecting the flank of Portsmouth some miles west across the marshes, the fort was later rebuilt in a star-shaped design’.

Fort Cumberland, Portsea, Hampshire

‘After the formation of the Royal Marine Artillery in 1804, the Companies that were attached to the Portsmouth Division of Royal Marines required a base to exercise and train with their field artillery and naval cannons. From 1817 Fort Cumberland was used, and from 1858 it became the Head Quarters for the RMA Division until Eastney Barracks was completed in 1867.’

Sometime in 1863 Joseph had either been discharged from the Marines or was back in Norfolk on leave. Whatever the case, he struck up a liaison with a local girl in Norwich called Ellen Dye, the daughter of shoemaker Robert Dye. Ellen became pregnant and delivered a baby daughter in Norwich in April 1864. Joseph and Ellen called the child Constane Campbell Dye. It was a usual pratice for unmarried mothers to give the father’s family name as a middle name. There must have been something real between Joseph and Ellen because two years later they had another child, this time a boy whom they called Robert Hugh Campbell Dye: Robert after Ellen’s father and Hugh after Joseph’s father. Why Joseph and Ellen never married we will never know. What we do know it that less than one one year after the birth of his son Robert, Joseph abandoned Ellen and married someone else: another Norfolk girl called Helen Eastoe. Helen was the daughter of Sprowston wheelwright Edmund Eastoe; she was two years Joseph’s senior. Given that Joseph too became a wheelwright it might well be that he was working with Helen’s father. Joseph and Helen married towards the end of 1867 in Norwich, and their first child, Joseph Hugh Eastoe Campbell, was born the next year.

Ellen and Joseph’s two other children were left to live with Ellen’s parents in Norwich.

Helen became pregnant again in the spring of 1869 and a son called Charles Alfred Campbell was born in Norwich in early 1870, but by this time as we will see Joseph had already left for America.

While all this was going on, Joseph’s three-year younger brother John had married as well. John had been given the name John Hugh Campbell Callf when he was born, because, as mentioned his parents weren’t able to marry while Hugh’s first wife was still alive. Joseph too had been given the name Callf at birth but all the family used the name Campbell in later years. John married under his full name of John Hugh Campbell Callf in late 1866 in Norwich, his wife was Mary Ann Hunn, the daughter of carpenter William Hunn. It’s probable that their first daughter Susana (later called Susie) was born in 1865 before their wedding. Two more children followed: Joseph Hugh in 1867 in Norwich and John in 1869 in Holborn in London. Mary Ann’s parents had moved to London and she had moved with them when her husband went to America with his brothers sometime in 1869.

What took Joseph, John and their unmarried brother Robert to America? Did they know people there? Had Joseph been to the United States while in the Marines? Or had they just heard of the opportunities there? We don’t know. But went they did in 1869. The date of their emigration is found in a book published in 1881 called History of southeastern Dakota, in which there are short ‘biographies’ of the prominent citizens of the town of Yankton in that year. Here we find both Joseph and John; they were the owners of the only ‘foundry’ and ‘iron works’ in the town, trading under the name J & J Campbell. John Campbell, it is said, came to America in 1869 and having ‘located in Sioux City in 1872, he removed to Yankton in 1874’. Joseph’s entry tells us he ‘came to America in company with his brothers’. In the English census of 1871, John, Joseph and Robert are absent. Joseph’s wife Helen is listed living in Norwich with their two children and was said to be the ‘wife of wheelwright in N. America’.

New York Docks in 1872

I believe that the three brothers first lived in New York. There is an entry in the 1870 US Federal census for an English-born ‘carpenter’ called Joseph Campbell, aged 30, living in Ward 20 District 3. This might or might not be our man. Most likely what happened is that the brothers were in New York and once established there wrote back home asking their wives to join them; possibly sending the money for the trip too. When their families arrived in October 1872 they then moved west, possibly first to Sioux City in Iowa and then to Yankton in the Dakota Territory. It is of course possible that the brothers had already made their way out west and that their families had to make the overland trip to join them alone. Remember John’s ‘biography’ says he located in Sioux City in 1872.

The families probably went west by train, first to Sioux City then to Yankton. The railway had reached Sioux City in 1868: ‘The first train rumbled into town. The date, March 9, 1868, was the cause of much local celebrating. “SAVED AT LAST!” read the Sioux City Journal headline.’ By 1873 it had reached Yankton: ‘In 1873 a railroad line was expanded to Yankton, Dakota Territory. Yankton then became the end of the railroad line and much of the business growth Sioux City had gained moved up river.’

The Dakota Territory was established in 1861. It didn’t become a state (actually two states) until 1889.

The Dakota Territory consisted of the northernmost part of the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase of the United States. The name refers to the Dakota branch of the Sioux tribes which occupied the area at the time. Most of Dakota Territory was formerly part of the Minnesota and Nebraska territories. When Minnesota became a state in 1858, the leftover area between the Missouri River and Minnesota’s western boundary fell unorganized. When the Yankton Treaty was signed later that year, ceding much of what had been Sioux Indian land to the U.S. Government; early settlers formed an unofficial provisional government and unsuccessfully lobbied for United States territory status. Three years later soon-to-be-President Abraham Lincoln’s cousin-in-law, J.B.S. Todd, personally lobbied for territory status and Washington formally created Dakota Territory. It became an organized territory on March 2, 1861. Upon creation, Dakota Territory included much of present-day Montana and Wyoming.

Yankton in 1876

The Territory’s capital was the town of Yankton; in size it was bigger than most European countries. In the early 1870s the white population only amounted to about 12,000 and Yankton itself, the biggest settlement, had just 3,000. This was still very much the land of Native American Indians, particularly, though not exclusively, the Lakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne. As elsewhere the Americans would soon start ethnically cleansing the territory and reducing the Native people to a small underclass.

In 1868 the United States Government had signed a Treaty at Fort Laramie in Wyoming (also called the Sioux Treaty of 1868) with the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation. This was to guarantee ‘Lakota ownership of the Black Hills, and further land and hunting rights in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana. The Powder River Country was to be henceforth closed to all whites’.

Dakota Territory

When the Campbells arrived in Yankton, which in Joseph’s case I would date to 1873 because his daughter Charlotte was born in Yankton in January 1874, Dakota was witnessing the first years of a huge wave of immigration called the Great Dakota Boom.

As the economic depression of 1873 abated, the railroads took a new interest in this virgin territory. Although the federal government made no land grants in Dakota as in other territories, there were plenty of opportunities for profit in the founding of new towns. Town lots came dear in railroad terminus, and since the companies had the advantage of knowing where the track would be laid next, they invariably held title to the choicest lots. Of the 285 towns which were platted during the Boom period, 138 of them were founded by the railroads. 89 more were platted along the railroad right of way by private land companies.

These were placed every seven to ten miles along the tracks to provide a market-place for the farmers within driving distance by team and wagon. While the presence of a railroad meant instant prosperity for the community there was often distrust of the giant monopolies which could place the depot, tracks and outbuildings to their best advantage rather than the town’s. For this reason, future town sites were often discreetly bought up by agents of the company and a certain amount of skulduggery was not uncommon in the rush for profits.

The influence of the railroads cannot be overemphasized in both the rapid settlement and ultimate success of Dakota Territory. They tended to neutralize the negative weather and conditions by bringing in fuel, food, fencing and building materials – all unavailable on the treeless plains. And of course the railroads brought the farmer closer to his marketplace.

People flooded in from the East and from Europe, particularly German Russians, Scandinavians as well as Irish and English. ‘Many a Scandinavian or northern European immigrant first heard of this new land of opportunity from a railroad brochure, poster or flier printed in his own native language.’

‘Unlike earlier pioneers who formed caravans of prairie schooners across the plains, these settlers came by rail, often to within just a few miles of their final destination,’ as most likely did the Campbells. But while the Scandinavians tended to become rural farmers, the English tended to settle in Yankton and other growing settlements.

But in 1873/4 most of the land in Dakota, and particularly the Black Hills, still belonged to the Native American Nations. They had, for sure, already suffered many a defeat at the hands of the U.S. Army, and were on the path to almost total subjugation and annihilation, but they could still live and hunt in the Black Hills, a land sacred to them. This would soon change; the reason being, as usual, gold.

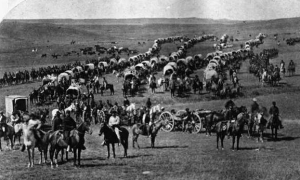

Custer’s Black Hills expedition in 1874

As Ernest Grafe writes in The 1874 Black Hills Expedition:

There had always been rumors of gold here, however, and by 1874 the frontier settlements were putting pressure on the government to permit exploration. A financial panic was adding to the pressure, and it’s possible that the railroads were working behind the scenes to generate more business. It was in this atmosphere that Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan ordered a reconnaissance of the Black Hills, allegedly to look for a site on which to build a fort. The reconnaissance would be led by Gen. George Armstrong Custer, who brought along a photographer, several newspapermen and two prospectors — but who never once mentioned building a fort.

Custer’s expedition triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush. But Custer had first come to Dakota in April 1873 ‘to protect a railroad survey party against the Lakota’. He and his Seventh cavalry were first stationed in Yankton, whose citizens had rescued them when they were caught in a tremendous snow storm. They would stay in Yankton until May 1874 when they set out on their expedition to the Black Hills. There is no doubt that Joseph Campbell and his family would have seen Custer, his officers and the men of the cavalry on many occasions. Little would they know the fate that awaited them.

After the expedition miners kept arriving to try their luck in the diggings in the Lakota’s Black Hills. They usually come via Yankton, and Joseph and John Campbell would, as the only ‘founders’ and iron workers in town, have supplied many of them with the iron tools and machinery they needed.

General Custer

The U.S. Government made noises about stopping this invasion of miners into the Indians’ reservations, but once mining and money was involved their resolve flagged. I won’t retell the whole sorry tale here, but in 1876 General Custer attacked an Indian settlement at Little Big Horn. It was a mistake: there were many more Lakota and Cheyenne warriors there than he had imagined and Custer’s Seventh Cavalry companies were killed to a man. Sitting Bull and his warriors had secured the last victory Native American Indians would ever have over the invading Americans.

News of the death of Custer and his men would have soon reached Yankton. The population of the town were scared, including the Campbell brothers and their families. But their fears were unfounded. The American government despatched more troops and over the coming months started piteously to hunt down the various Indian groups which had dispersed after Little Big Horn. Sitting Bull fled north and found sanctuary for a time in the ‘Land of the Great Mother’: Canada. The U.S. government seized the Black Hills land in 1877.

Sitting Bull

You can read about this sad and brutal history in many books, or watch PBS’s excellent documentary series The West. The battle of Little Big Horn was the last time Native Americans were able to resist the American invasions of their land. From now on the Lakota and the other local tribes were herded into smaller reservations and had to rely on patchy deliveries of ‘rations’ to survive. Their children were to be shipped off to faraway schools to be deracinated; stripped of their language and culture and introduced to the dubious benefits of Christianity. ‘How the West was won’ is a brutal and sad tale. It tells us more about American savagery than it does about the ‘barbarous’ Indians.

In 1880 – 1882 Joseph and John Campbell were still in Yankton running the ‘Yankton Iron Works’. Since his family’s family arrival in Dakota Joseph and Helen had had four more children: Charlotte in 1874, John Robert in 1877, Constance Elizabeth in 1880 and Helen in 1882. His brother John and his wife Mary Ann had had two: Martha Caroline in 1878 and Robert Hugh in 1879.

Where had their younger brother Robert been all this time? Although he had come to America with his brothers, the first mention of him I can find is in 1895 in Sioux City, Iowa. He would marry seventeen year-old Kansas-born girl Ada Maud Parsons in Sioux City in 1898 and have a son called William Herbert the next year. Perhaps Robert had spent more than twenty years seeking his fortune, first in the Black Hills and then elsewhere before marrying in Sioux City aged thirty-eight? We don’t know. Sometime before 1910 Robert and Ada ‘divorced’ and she took their son to live with her parents in Marshall, Iowa, but by 1915 she was back in Sioux City with her parents, by now, she said, a ‘widow’. In 1920, still with her parents, she said she was ‘single’. But Robert wasn’t dead, he was back in Sioux City living with Ada in 1925 and 1928 before disappearing again by 1930 when Ada was back with her parents but still said to be ‘married’. Nothing more is heard of Robert. Ada eventually moved to California where she died in 1969 aged eighty-eight.

Sioux City, Iowa in 1873 as the Campbells first saw it

But what of Joseph and John and their families who we left in Yankton? John took his family back to Sioux City in the mid 1880s where he and Mary Ann had two more children: William Arthur in 1887 and Mildred in 1889. He was still there in 1910, aged 66 and unemployed, living with his widowed daughter Martha Gardner and her children and his divorced daughter Mildred Lowe. After that there is no trace of John, but his wife Mary Ann (nee Hunn) died in 1915 and is buried in Sioux City’s Graceland Cemetery.

Joseph too left Yankton. Possibly by way of Sioux City the family moved to Chicago in 1891. In 1900 the family are living in Chicago’s 12th Ward and Joseph is working as an ‘engineer’ in a stationer’s printing shop. Helen was said to have had eleven children (I can only identify six), of which five were still alive. Perhaps it is not surprising therefore that Helen died two years later aged sixty-three of ‘Hemiplegia’, most probably brought on by a stroke.

Joseph lived on. He was by now in his sixties, a former Royal Marine gunner, a wheelwright, a founder, a machinist and an engineer. After thirty years in America did he ever, I wonder, think of the family he had abandoned back in England? In Dakota he had christened a daughter Constance. It was a family name and he had given the same name to his first child with Ellen Dye back in 1864. Did he ever think of his first two children: Constance Campbell Dye and Robert Hugh Campbell Dye? Maybe yes, maybe no. I sometimes think about this because Joseph was my 2nd great grandfather, and his first child Constance Campbell Dye was my great grandmother. Already by the time his wife died in 1902, Joseph had ten grandchildren back in Norfolk, another was to follow in 1905.

Mankato in the1920s

Whatever the case, Joseph’s amazing life was far from over. In 1910 he was still working as an engineer in a Chicago ‘water works’. In 1920, aged seventy-nine, he was living with his son John’s family but still working as an engineer! Sometime in the 1920s Joseph had to call time on his long working life and he moved to North Mankato in Nicollet County, Minnesota. He spent his last years living with his granddaughter Grace Michel, her husband Bernard, and their children. It was here in Mankato a long way from Norfolk that Joseph Hugh Campbell died on 26 October 1931 aged ninety-two; he was buried with his wife and son Charles back in Chicago’s Forest Home Cemetery.

Joseph has a lot of descendants in the United States plus many in England too, including myself. What had become of Joseph’s first ‘love’ Ellen Dye and his two children Constance and Robert? Ellen married Norwich shoemaker Henry Bell and had five children with him. She continued to work as a silk weaver in Norwich until her death in 1920 aged seventy-six. Joseph’s son Robert married Flora Hoy Davidson in 1892 but they had no children. He died in Norwich in 1948. Joseph’s first born child Constance Campbell Dye on the other hand married Norwich shoemaker Henry Allen in 1882 and had eleven children over the next twenty-three years, while also, like her mother, working as a silk weaver. Her fourth child, my grandfather, was born in 1887; he was named Robert after Constance’s grandfather Robert Dye.

Joseph Hugh Campbell led an amazing life!

Robert Allen (Joseph’s grandson and my grandfather) with Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin