‘I will bury him myself. And even if I die in the act, that death will be a glory… I have longer to please the dead than please the living here.’ Antigone, Sophocles.

Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk, unfurled the Royal Banner in Carlisle in February 1537. He was declaring martial law in the North of England. Martial law wasn’t really law at all; it was simply a suspension of the accepted process and procedures of English law. It meant that anyone taking part in or supporting a rebellion, or defying the crown in any way, could be summarily dealt with as a traitor. They could be executed without the bother or uncertainties of a jury trial.

Royal Banner of Henry the Eighth

Howard had taken it upon himself to ‘unfurl the banner’ in the name of King Henry VIII, whose authority had been challenged by the recent uprising in Lincoln, by the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’ in Yorkshire, Northumberland and Durham and by a serious rebellion in Westmorland and Cumberland. Henry had broken with Rome and, advised by the unpopular Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell, was setting about dissolving and robbing catholic England’s monasteries and abbeys. He was also increasing the tax burden of the people and encouraging the theft of common land via private enclosure. All of these measures were deeply unpopular over great swathes of the country. They were obviously resented and resisted by monks, friars and other clergymen, but also by gentry and commoners as well – though for different reasons.

The uprising in Lincoln in late 1536 had managed to muster thousands of people to the cause but had ended after just two weeks. Just as the King’s representatives were about to wreak their revenge on the Lincoln rebels, a more serious challenge arose: the people of Yorkshire and surrounding parts of Northumberland, Durham and Lancashire had also rebelled. Under the leadership of lawyer Robert Aske, this was essentially a conservative protest and one that the rebels wanted, if at all possible, to keep non-violent. Aske himself christened it the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’, a name that perhaps unfortunately has stuck. The rebels didn’t want to challenge the King’s right to rule, rather they wanted to pressure him to stop the dissolution of the monasteries, restore the link with Rome and suppress the spread of Lutheran versions of Protestantism. They also hoped that some of Henry’s hated advisers would be removed, particularly Chancellor Thomas Cromwell, who they blamed for both the religious policies and, as importantly, their own worsening economic plight.

The Holy Wounds Banner of the Pilgrimage of Grace

In this sense the Pilgrimage of Grace was both a social and a religious revolt. The impetus came from below, from the ‘commoners’, but some of the local gentry joined in willingly, while others needed to be coerced.

Under Aske’s leadership, the leaders of the rebellion called themselves ‘Captains of Poverty’ or sometimes, in the case of monks and priests, ‘Chaplains of Poverty’. These captains started to call out the northern ‘host’, usually a thing done by the king or the local barons. Their numbers swelled, to reach around 28.000 – 35,000 by October 1536. They were disciplined and organized and more than enough to face down, and defeat if necessary, the 4,000 mercenary troops, under the Duke of Norfolk, who Henry had sent to put them down. The rebels had captured Pontefract castle without much trouble.

Robert Aske – Leader of the Pilgrimage of Grace

This isn’t the place to retell the events and causes of the Pilgrimage of Grace. There are many fine histories of what happened. In brief, Norfolk knew he couldn’t defeat the rebels by force of arms, so he prevaricated and seemed to play along with, even sympathize with, their demands. A truce was called on 27 October at Doncaster Bridge and on 6 December Norfolk promised a royal pardon in the name of the King. He also promised that many of the rebels’ demands would be met. Eventually, and not without great deliberation, the northern rebel host dispersed and the Pilgrimage was effectively over. It is only in retrospect that we can judge them naive.

All this was not to Henry’s liking. Henry’s instinctive and invariable reaction was always to crush any opposition, not to make concessions or compromises. He soon reneged on the pardon and had many of the leaders or sympathizers of the revolt executed. He never took England back to Rome and he redoubled his drive to dissolve the monasteries and expropriate and appropriate their considerable wealth.

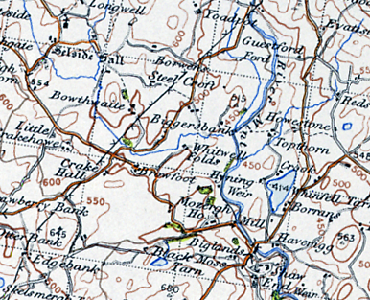

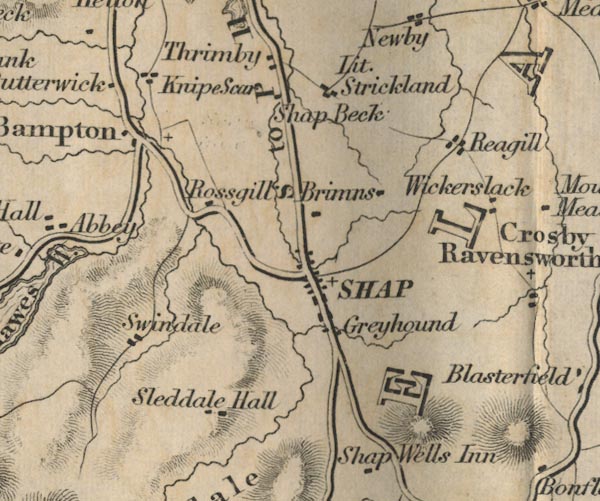

Let us return to events in Westmorland or Cumberland (which together I rather anachronistically will call Cumbria). This was a region that the Duke of Norfolk himself was to call the ‘poorest shire in the realm’. During the Pilgrimage appeals had been made to the people of these counties to join in and to take the Pilgrims’ Oath. Local ‘Captains’ were appointed and some of them were to go to Yorkshire on at least two occasions to consult with Robert Aske and the other leaders. Two of the most prominent Cumbrian captains were Nicholas Musgrave and Robert Pullen, but several others went as well.

The Cumbrian captains started to gather support. To try to remain anonymous they usually called themselves ‘Captain Poverty’ – like their Yorkshire colleagues. Eventually a force of 15,000 was gathered and was planning to march on Carlisle, the administrative and military centre of the ‘West Marches’. But before they could progress any further, news came that the Pilgrimage was over and, despite the fact that Sir Francis Bigod and John Hallam tried to resurrect it, unsuccessfully as it turned out, the Cumbrian rebel host disbanded and returned home.

Over Christmas 1536, and into the early New Year, the commoners started to fear that their local gentry had abandoned them and that they had slipped off to London to declare their allegiance to King Henry. They were right. Madeleine Hope Dodds and Ruth Dodds wrote in 1915, in their still seminal two volume study The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Exeter Conspiracy:

The chief reason for the agitation was the departure of so many gentlemen to court. The commons distrusted the King, who might have the gentlemen beheaded, and they distrusted the gentle men, who might betray them to the King. When the gentlemen were away, the bailiffs and other officers found it impossible to keep order.

And that might have been that were it not for Henry’s reprisals. He wanted all the leaders of the Pilgrimage hunted down and executed as traitors. In early January 1537, it became known that ‘Captains’ Nicholas Musgrave and Thomas Tibbey were in the Westmorland town of Kirkby Stephen. On 6 January, Thomas Clifford, the ‘bastard son’ of Henry Clifford, the first earl of Cumberland, was sent to the town to capture them. ‘Musgrave was warned and with Thomas Tibbey he took refuge in the church steeple, so defensible a position that Clifford was obliged to withdraw without his prisoners’. This, we are told, ‘stirred the country greatly’. A watch was to be kept for them in every town. ‘The men of Kirkby Stephen plucked down all the enclosures in their parish and sent orders to the surrounding parishes to follow their example.’

Things started to get tense. In Cumberland, one of the King’s men, Sir Thomas Curwen, wrote that ‘The west parts, from Plumland to Muncaster, is all a flutter’. He told how ‘on Saturday 13 January a servant of Dr Legh came to Muncaster. The whole country rose and made him prisoner. He was carried to Egremont and thence to Cockermouth. A great crowd filled the market-place, crying, “Strike off his head!” and “Stick him!”

Kirkby Stephen Church

The region was in ferment and it only needed a spark to set it alight. This spark was provided on 14 February when ‘bastard’ Thomas Clifford returned to Kirkby Stephen, once again trying to capture Musgrave and Tibbey. This time he came with a group of ‘mosstroopers from the waters of Esk and Line ’. These were rough border reivers, ‘strong thieves of the westlands’, with a penchant for violence.

Musgrave and Tibbey fled to their old fastness in the steeple, and there defied their pursuers. The townsfolk took no part either for or against the rebels, but while Clifford and some of his men were debating how to take their quarry, the rest of the riders, following their inbred vocation, fell to plundering. This was more than flesh and blood could bear. The burgesses caught up their weapons and fell upon the spoilers, causing a timely diversion in favour of the men in the steeple. Scattered about the narrow streets of the town, the horsemen were at a disadvantage and soon showed that their prowess was not equal to their thievishness. Two of the townsmen were killed in the skirmish, but their enraged fellows drove the borderers from the town and followed up their retreat until they were forced to take refuge in Brougham Castle.

Moss Troopers

Musgrave and Tibbey had escaped again. But having witnessed the brutality of the King’s forces, the local people realized that they would get no quarter or justice either from the King or the local nobility. They could expect no fair hearing of their economic or other grievances. ‘The commons saw that they were committed to a new rebellion, although they had risen in defence of their property ; indeed, a panic seems to have spread through the countryside that they would all be treated like the people of Kirkby Stephen. The two captains raised all the surrounding country and sent the following summons to the bailiff of Kendal, whom they knew to be on their side’:

To the Constable of Mellynge. ‘Be yt knowen unto you Welbelovyd bretheren in god this same xii day of februarii at morn was unbelapped on every syde with our enimys the Captayne of Carlylle and gentylmen of our Cuntrie of Westrnerlonde and haithe destrowed and slayn many our bretheren and neghtbers. Wherfore we desyre you for ayde and helpe accordyng to your othes and as ye wyll have helpe of us if your cause requyre, as god forbede. this tuysday, We comande you every one to be at Kendall afore Eight of the clok or els we ar lykly to be destrowed. Ever more gentyll brether unto your helpyng honds. Captayn of Povertie. ‘

None of the local gentry joined them and very few priests. They were more afraid of losing their aristocratic privileges and the wrath of the King than they were concerned about Henry’s religious reforms. The ‘commoners’ were on their own. Their plans were simple. ‘They had long before decided that the first step in case of a new rebellion was to seize Carlisle.’

Thomas Howard 3rd Duke of Norfolk

The Duke of Norfolk was still in Yorkshire continuing his clean-up and reprisals after the Pilgrimage of Grace. Carlisle was commanded by Sir John Lowther, Thomas Clifford and John Barnsfeld. They were out-numbered and they were worried. They knew that they needed the help of Sir Christopher Dacre, who, in the absence of his nephew Lord William Dacre, welded the most power in the area. Christopher Dacre’s loyalty to the crown was still much in doubt and the Clifford and Dacre families were old adversaries – enemies even. On 15 February the three Carlisle commanders wrote to Sir Christopher Dacre:

In the King our sovereign lord’s name we command you that ye with as many as ye trust to be of the King’s part and yours, come unto this the King’s castle in all goodly haste possible, for as we are informed the commons will be this day upon the broad field … further that ye leave the landserjeant with the prickers of Gillisland so that he and they may resist the King’s rebels if the said prickers of Gillesland will take his part, or else to bring him … and that ye come yourself in goodly haste. (Castle, of Carlisle, 15 February at 10 hours.)

When the Duke of Norfolk, who was in Richmond, heard about the danger in Cumbria, he too wrote to Dacre on the same day:

Cousin Dacres, I know not whether you received the letter I sent you yesterday. I hear those commons now assembled draw towards Carlisle, and doubt not you will gather such company as you may trust and, after your accustomed manner, use those rebels in a way to deserve the King’s thanks and to aid your nephew, my very friend, whom I look for every hour. I will not instruct you what ye shall do, for ye know better than I. Spare for no reasonable wages, for I will pay all. And spare not frankly to slay plenty of these false rebels; and make true mine old sayings, that ‘Sir Christopher Dacre is a true knight to his sovereign lord, an hardy knight, and a man of war’. Pinch now no courtesy to shed blood of false traitors; and be ye busy on the one side, and ye may be sure the duke of Norfolk will come on the other. Finally, now, Sir Christopher, or never. (Richmond, 15 Feb.) Your loving cousin if ye do well now, or else enemy for ever.

Norfolk had written to the king the previous day informing Henry that ‘when Cumberland’s bastard son, deputy captain of Carlisle, came to take two traitors at Kirkby Stephen, they keeping the steeple, his horsemen, in great part strong thieves of the Westlands, began to spoil the town, and the inhabitants rose to defend both their goods and the traitors. A skirmish ensued, in which one or two rebels were slain, and Thomas my lord’s bastard son, was forced to retire to Browham (Brougham) castle. The country has since risen, some say 4,000 or 5,000 together, and are sending for others to aid them.’

Norfolk thought that ‘no such thing would have occurred if this enterprise had been handled as it was promised’.

By 16 February about 6,000 local Cumbrians were camped on Broadfield Moor, a few miles south of Carlisle. They were ‘more or less effectively armed and mounted’. They knew Carlisle was, as it has always been, the key to controlling the region. They didn’t have gentry leadership, but in no way were they a rabble, as too many histories have disparagingly called them. They were in fact the very same people, the same ‘host’, which the local barons would usually call out when they needed military support. Clifford and the other commanders of the town had been busy rallying the local ‘artisans’ to the defence of the town. The Cumbrian host didn’t really know how to go about attacking or besieging a fortified town.

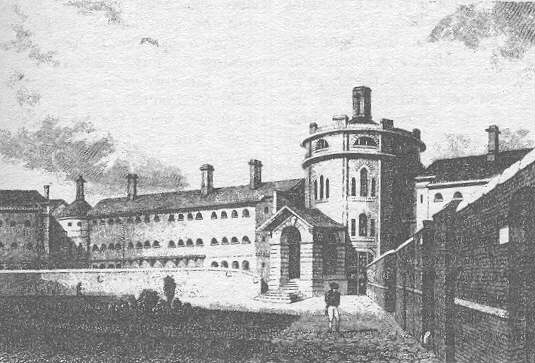

Carlisle Castle

On Saturday 17 February, the host prepared for the assault on Carlisle. ‘The rebels carried a cross as their banner principal… It does not seem to have been such a vigorous attack as the word now implies. They approached within bow-shot, and showered arrows on the defenders who appeared on the city walls. This went on until they exhausted their supply of arrows, when they retired a little way to consider what to do next.’

After the failure of their attempt to take the town, the rebels were considering how best to attack again when, suddenly, Sir Christopher Dacre arrived on the scene with ‘five hundred border spearmen’ – called ‘prickers’. The commons broke and turned to flee. This emboldened the defenders and they sallied forth from Carlisle. Together with Dacre’s men they set about the now fleeing commoners. The mosstroopers were ‘in no mood to spare the countryfolk who had beaten them so ignominiously on Monday’.

The rejoicings in London were great. Sir Christopher Dacre was the hero of the hour. It was said that he had slain 700 rebels or more and taken the rest prisoners, hanging them up on every bush.

Exactly how many of the commoners were massacred is not known. Perhaps not the 700 reported. But compare this with the fact that in the whole of the more famous Pilgrimage of Grace (I exclude the later reprisals) there had only been one death – and that was accidental. Hundreds of prisoners were taken back to Carlisle, including it seems Thomas Tibbey, but not Nicholas Musgrave. The rest of the host fled back to their homes or went into hiding. Christopher Dacre had proved his loyalty and was later rewarded for his decisive intervention.

On the day of the attack and subsequent massacre, the Duke of Norfolk was still at Barnard’s Castle in Yorkshire and had raised 4,000 men – ‘everyone they could trust.’ But news soon reached him that this ‘splendid little army’ would not be needed. Norfolk was delighted. He wrote to King Henry that Christopher Dacre had ‘shown himself a noble knight’ and that ‘seven or eight hundred prisoners were taken.’ He was, he wrote, ‘about to travel in all haste to Carlisle to see execution done.’

Norfolk arrived at Carlisle on Monday 19 February. This is when he ‘unfurled the banner’ and imposed martial law, not just on Cumbria but on the whole of the North of England. He used the pretext of the Carlisle events to be better able to punish those involved in draconian fashion, as well to be able to more easily and brutally punish those involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace itself. Norfolk reported that: ‘There were so many prisoners in the town that he found great difficulty in providing for their safe-keeping.’ ‘He wrote that night to the Council to promise that if he might go his own way for a month he would order things to the King s satisfaction. It would take some time, because he must himself be present at all the convictions and proceed by martial law, and there were many places to punish.’ He added, significantly, that ‘not a lord or gentleman in Cumberland and Westmorland could claim that his servants and tenants had not joined in the insurrection.’

Proclamations were issued which ‘commanded all who had been in rebellion to come to Carlisle and submit themselves humbly to the King’s mercy.’ ‘The country people began to straggle into the city in scattered, dejected bands. They had lost their horses, harness, and weapons in the chase; they were in instant fear of a traitor’s death for themselves, and of fire, plunder, and outrage for their homes and families.’ Norfolk wrote that ‘they were contrite enough to satisfy any tyrant’ and ‘if sufficient number of ropes might have been found (they) would have come with the same about their necks’

Taking advice from the local lords, Norfolk chose seventy-four of the ‘chief misdoers’. ‘That is of the braver and more determined of them, and turned the rest away without even a promise of pardon’.

On 21 February, Norfolk wrote to Thomas Cromwell: ‘The poor caitiffs who have returned home have departed without any promise of pardon but upon their good a bearing. God knows they may well be called poor caitiffs; for at their fleeing they lost horse, harness, and all they had upon them and what with the spoiling of them now and the gressing (taxing) of them so marvellously sore in time past and with increasing of lords’ rents by inclosings, and for lack of the persons of such as shall suffer, this border is sore weaked and specially Westmoreland; the more pity they should so deserve, and also that they have been so sore handled in times past, which, as I and all other here think, was the only cause of this rebellion.’

Norfolk knew that if he left justice to the mercy of local juries he probably wouldn’t be able to execute as many as both he and, importantly, the King and Thomas Cromwell wanted. ‘Many a great offender’, he said, would be acquitted if juries were called. He was quite honest about this. He later wrote to the King:

All the prisoners were condemned to die by law martial, the King’s banner being displayed. Not the fifth part would have been convicted by a jury. Some protested that they had been dragged into rebellion against their will. The most part had only one plea, saying, ‘I came out for fear of my life, and I came forth for fear of loss of all my goods, and I came forth for fear of burning of my house and destroying of my wife and children… A small excuse will be well believed here, where much affection and pity of neighbours doth reign. And, sir, though the number be nothing so great as their deserts did require to have suffered, yet I think the like number hath not been heard of put to execution at one time.

As the Dodds wrote: ‘They had not, in fact, turned against the law, they had risen to defend all that the law should have defended for them from Clifford’s police, the thieves of the Black Lands.’

Henry the Eighth

Henry was pleased with what Norfolk and the defenders of Carlisle had done. His reply to Norfolk on the 22nd was blunt and brutal. He started with his thanks: ‘We have received your letters of the 16th, about the new assembly in Westmoreland, and your others of the 17th by Sir Ralph Evers, touching the valiant and faithful courage of Sir Chr. Dacres in the overthrow of the traitors who made assault upon Carlisle, reporting also the good service done by Thomas Clifford, and the perfect readiness of all the nobles and gentlemen in Yorkshire and those parts to have served in your company against them. We shall not forget your services, and are glad to hear also from sundry of our servants how you advance the truth, declaring the usurpation of the bishop of Rome, and how discreetly you paint those persons that call themselves religious in the colours of their hypocrisy, and we doubt not but the further you shall wade in the investigation of their behaviours the more you shall detest the great number of them and the less esteem the punishment of those culpable… We desire you to thank those that were ready to have served us. We have thanked Sir Chr. Dacres in the letters which you shall receive herewith, and will shortly recompense him in a way to encourage others.’

Referring to Norfolk’s decision to declare martial law, Henry continued:

We approve of your proceedings in the displaying of our banner, which being now spread, till it is closed again, the course of our laws must give place to martial law… Our pleasure is, that before you shall close up our said banner again, you shall, in any wise, cause such dreadful execution to be done upon a good number of the inhabitants of every town, village, and hamlet, that have offended in this rebellion, as well by the hanging them up in trees, as by the quartering of them and the setting of their heads and quarters in every town, great and small, and in all such other places, as they may be a fearful spectacle to all other hereafter, that would practise any like mater.

Finally, as these troubles have been promoted by the monks and canons of those parts… you shall without pity or circumstance, now that our banner is displayed, cause the monks to be tied up without further delay or ceremony.

Anyone who had participated in the uprising and escaped was still pursued. On February 28 the earls of Sussex and Derby and Sir Herbert Fitzherbert wrote to the King from Warrington in Lancashire: ‘There came lately to Manchester one William Barret, a tanner dwelling in Steton in Craven, who declared to the people that my lord of Norfolk at this his being in Yorkshire would, as he heard, either have of every plough 6s. 8d. or take an ox of every one that would not pay, and that every christening and burying should pay 6s. 8d. Being apprehended and brought before us, he confessed he was one of those who made the late assault at Carlisle and shot arrows at those in the town, and that the constables of the townships, after divers bills set upon church doors, warned him and his company so to rise, alleging that one of the Percies would shortly join them. We think he deserves the most cruel punishment; but Mr. Fitzherbert says the words are no ground for putting him to death, and that he cannot be indicted in one shire for an offence committed in another; we therefore forbear to proceed till we know your pleasure.’ (Warrington, 28 Feb.)

This brings us to the main point of this short article. What was to be the fate of the 74 rebels that Norfolk and the local lords had picked for summary execution? Henry had ordered Norfolk to hang ‘them on trees, quartering them, and setting their heads and quarters in every town’. We don’t know how many of them, if any, were actually hung, drawn and quartered as Henry had clearly wanted, and as was often the case for traitors under martial law. The punishment itself was described by Chronicler William Harrison as follows:

The greatest and most grievous punishment used in England for such as offend against the State is drawing from the prison to the place of execution upon an hurdle or sled, where they are hanged till they be half dead, and then taken down, and quartered alive; after that, their members and bowels are cut from their bodies, and thrown into a fire, provided near hand and within their own sight, even for the same purpose.

Gibbet Irons

It’s most likely that none of the rebels were hung, drawn and quartered. Even Robert Aske was finally spared this fate. They were in all probability all ‘hung in chains’. When Norfolk later wrote to Thomas Cromwell, he said, ‘All in this shire were hung in chains.’ What was hanging in chains? It was a form of punishment and deterrence used for centuries in England until it was abolished in 1834. An eighteenth century French visitor to England, Cesar de Saussure, described what happened:

There is no other form of execution but hanging; it is thought that the taking of life is sufficient punishment for any crime without worse torture. After hanging murderers are, however, punished in a particular fashion. They are first hung on the common gibbet, their bodies are then covered with tallow and fat substances, over this is placed a tarred shirt fastened down with iron bands, and the bodies are hung with chains to the gibbet, which is erected on the spot, or as near as possible to the place, where the crime was committed, and there it hangs till it falls to dust. This is what is called in this country to ‘hang in chains’.

But in Tudor times the punishment was often even more barbaric. People were frequently hung alive in chains and they first starved in agony before putrefying on the gibbet. How many of the rebels were ‘gibbeted’ alive and how many dead is not known. The point of these executions was of course not simply to kill people, it was also to make them and their relatives suffer and to be so terrifying that it would act as a deterrent to any future challenges to royal authority. The cadavers were not allowed to be removed and buried. They should remain rotting, sometimes for years, in full sight of their communities. For the condemned and their relatives this was not just a question of suffering and grief, it was also a matter concerning their eternal souls: Many still believed that the resurrection of the dead on judgement day ‘required that the body be buried whole facing east so that the body could rise facing God’

Hanging in Chains

The rebels were hanged (in chains) in their own villages, ‘in trees in their gardens to record for memorial’ the end of the rebellion.

Twelve were hanged in chains in Carlisle for the assault on the city, eleven at Appleby, eight at Penrith, five at Cockermouth and Kirkby Stephen, and so on; scarcely a moorland parish but could show one or two such memorials. Some were hanged in ropes, for iron was ‘marvellous scarce’ and the chain-makers of Carlisle were unable to meet the demand. The victims were all poor men, farm hands from the fields and artisans of the little towns; probably the bailiff of Embleton was the highest man among them. Only one priest suffered with them, a chaplain of Penrith.

Once the executions of these poor men had been carried out, in village after village throughout Cumberland and Westmorland, their women wanted to bury their husbands, sons and fathers. Like latter-day Antigones, they thought this to be their natural right and duty. But Henry’s law, like that of Creon, forbade it. At great risk to their own safety and lives, the women crept out at night and cut down their men and secretly buried them.

In May, when Norfolk heard that ‘all’ the rebels’ bodies had been cut down and buried, he ordered the Cumberland magistrates to seek out the ‘ill-doers’. They sent him nine or ten confessions in reply, but he did not consider these nearly enough: ‘It is a small number concerning seventy-four that hath been taken down, wherein I think your Majesty hath not been well served.’

The Dodds write: ‘Of all the records these brief confessions are the most heart-breaking and can least bear description. The widows and their neighbours helped each other. Seven or eight women together would wind the corpse and bury it in the nearest churchyard, secretly, at nightfall or day break. Sometimes they were turned from their purpose by the frightened priest, and then the husband’s body must be buried by a dyke-side out of sanctified ground, or else brought again more secretly than ever and laid in the churchyard under cover of night. All was done by women, save in two cases when the brother and cousin of two of the dead men were said to have died from the “corruption” of the bodies they had cut down.’

Norfolk asked the King what he should do with these offenders. They were all, he said, women: ‘the widows, mothers and daughters of the dead men’. Thomas Cromwell was displeased, suspecting that Norfolk had ordered or countenanced this. Norfolk tried to placate him and shift any blame to the Earl of Cumberland. He wrote to Cromwell:

I do perceive by your letter that ye would know whether such persons as were put to execution in Westmorland and Cumberland were taken down and buried by my commandment or not: undoubtedly, my good lord, if I had consented thereunto, I would I had hanged by them; but on my troth, it is 8 or 9 days past since I heard first thereof, and then was here with me a servant of my lord of Cumberland called Swalowfield, dwelling about Penrith, by whom I sent such a quick message to my said lord, because he hath the rule in Cumberland as warden, and is sheriff of Westmorland and hath neither advertised me thereof, nor hath not made search who hath so highly offended his Majesty, and also commanding him to search for the same with all diligence, that I doubt not it shall evidently appear it was done against my will.

We don’t know what the subsequent inquiries about these women’s actions disclosed and what, if any, were the consequences.

Henry’s Field of the Cloth of Gold

This brutal episode in English history is usually given scant mention in histories of the period, particularly in histories of Henry VIII – concerned as they depressingly are with political machinations, battles and the deeds of ‘great men’. Yet surely such events tell us more about the real history of England, or better said the real history of the English people, than do Henry’s dealings with the Holy Roman Emperor, the Papacy, his opulent and ostentatious ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’ or his tedious litany of marriages?

Of course the Pilgrimage of Grace and the Cumbrian rebellion had failed – although taken together they were the most significant challenge Henry would ever face at home. But in the case of the Cumbrian rebellion, its significance does not lie in its success or failure. It lies in the fact that it is just another much neglected example of what happens when ordinary English people try to protest against the repression of their rulers, their economic pauperization or the suppression of their religious or other rights. As Leveller leader Colonel Thomas Rainborough was to write in the seventeenth century:

For really, I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore truly, sir, I think it’s clear, that every man that is to live under a government ought first, by his own consent, to put himself under that government.

Antigone buries her brother

What I find a pity is that Antigone’s poignant and courageous act of burying her brother, whether it really happened or not, has been studied and dissected for at least two thousand years. German Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel even saw it as a clash of right against right: familial natural right against the right of the state; others interpret it differently. Yet ‘only’ five hundred years ago, dozens of poor Cumbrian women did the same thing and ran the same risk as Antigone, but they are hardly remembered at all. Who would dare today to present their bravery and humanity as a clash of two equally valid rights?

Sources:

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 12; Madeleine Hope Dodds & Ruth Dodds, The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Exeter Conspiracy, (1915); M. L. Bush, The Pilgrimage of Grace: A Study of the Rebel Armies of October 1536, (1996); Michael Bush & David Bownes, The Defeat of the Pilgrimage of Grace: A Study of the Postpardon Revolts of December 1536 to March 1537 and Their Effect, (1999).

The old customs peculiar to Cumberland and Westmorland of “Whittlegate” and “Chapel Wage” have long since passed out of the list of obligations imposed, although the rector of Brougham might still, if he wished, claim whittlegate at Hornby Hall every Sunday. The parsons of the indifferently educated class already alluded to had to be content with correspondingly small stipends, which were eked out by the granting of a certain number of meals in the course of twelve months at each farm or other house above the rank of cottage, with, in some parishes, a suit of clothes, a couple of pairs of shoes, and a pair of clogs. Clarke gives the following explanation of the origin of the term: —

The old customs peculiar to Cumberland and Westmorland of “Whittlegate” and “Chapel Wage” have long since passed out of the list of obligations imposed, although the rector of Brougham might still, if he wished, claim whittlegate at Hornby Hall every Sunday. The parsons of the indifferently educated class already alluded to had to be content with correspondingly small stipends, which were eked out by the granting of a certain number of meals in the course of twelve months at each farm or other house above the rank of cottage, with, in some parishes, a suit of clothes, a couple of pairs of shoes, and a pair of clogs. Clarke gives the following explanation of the origin of the term: —

Just after the Great War started Norman and his brother Joseph, like so many other Cumberland Grisdales, joined the Border Regiment. Norman’s battalion was the newly-formed 6th (Service) Battalion. Just before the Keswick brothers left for war they posed with their parents and sister for a photograph. See here.

Just after the Great War started Norman and his brother Joseph, like so many other Cumberland Grisdales, joined the Border Regiment. Norman’s battalion was the newly-formed 6th (Service) Battalion. Just before the Keswick brothers left for war they posed with their parents and sister for a photograph. See here.

In late April, 1945 as the war in Europe was nearing its end, the Russians were approaching from the east and the British and Americans from the West in a race to get to Hitler’s headquarters in Berlin. Stalag Luft I was north of Berlin, so it was unsure at first which of the Allied fronts would reach them first. As the reports came in and the fighting got closer and closer to Barth, they soon realized that the Russians would be the ones liberating them. They soon began to hear the heavy cannon fire sounds of the Russian artillery getting closer and closer to them.

In late April, 1945 as the war in Europe was nearing its end, the Russians were approaching from the east and the British and Americans from the West in a race to get to Hitler’s headquarters in Berlin. Stalag Luft I was north of Berlin, so it was unsure at first which of the Allied fronts would reach them first. As the reports came in and the fighting got closer and closer to Barth, they soon realized that the Russians would be the ones liberating them. They soon began to hear the heavy cannon fire sounds of the Russian artillery getting closer and closer to them.

Interestingly though the ‘barony of Greystoke’ (to use the French title), which included Grisdale and Matterdale, seems to be one of the exceptions that proves the rule. Here a powerful local family with Norse roots and Norse names was able to reach an accommodation with the Norman colonizers. This was the family of Forne Sigulfson, who became the first Norman-sanctioned lord of Greystoke. (See my article about Forne

Interestingly though the ‘barony of Greystoke’ (to use the French title), which included Grisdale and Matterdale, seems to be one of the exceptions that proves the rule. Here a powerful local family with Norse roots and Norse names was able to reach an accommodation with the Norman colonizers. This was the family of Forne Sigulfson, who became the first Norman-sanctioned lord of Greystoke. (See my article about Forne

Christopher Grisdale was born in Dalton in 1828, the illegitimate and only son of Elizabeth (‘Betty’) Grisdale. Betty too had been born in Dalton in 1807, one of two children of Dalton-born Christopher Grisdale and his Yorkshire wife Ruth Hatterton. To link in with a known Grisdale family, Christopher Senior, who was born in 1776, was one of several illegitimate children of an Agnes Grisdale, and it’s nigh on certain that this Agnes was born in 1730 in Heversham, Westmorland to John Grisdale and his first wife Elizabeth Holme. John was later to move to Cartmel (in about 1739) and was thus the first Grisdale to inhabit this coastal area. I wrote about this family in a story called

Christopher Grisdale was born in Dalton in 1828, the illegitimate and only son of Elizabeth (‘Betty’) Grisdale. Betty too had been born in Dalton in 1807, one of two children of Dalton-born Christopher Grisdale and his Yorkshire wife Ruth Hatterton. To link in with a known Grisdale family, Christopher Senior, who was born in 1776, was one of several illegitimate children of an Agnes Grisdale, and it’s nigh on certain that this Agnes was born in 1730 in Heversham, Westmorland to John Grisdale and his first wife Elizabeth Holme. John was later to move to Cartmel (in about 1739) and was thus the first Grisdale to inhabit this coastal area. I wrote about this family in a story called

The Royal Cornwall Gazette reported on Saturday 18 February 1815:

The Royal Cornwall Gazette reported on Saturday 18 February 1815:

I’ll concentrate here on the Cumberland Grisdales. Because Grisdale is a place name, then the early people taking the name were most likely styled as such because they came from there and had most probably moved some way away. They would have been referred to, for example, as John or Richard of Grisdale (or in the Norman French version John or Richard de Grisdale), to distinguish them from other Johns and Richards living nearby. If people lived in the same place, say Grisdale itself, they’d be no need to say they were ‘of Grisdale’.

I’ll concentrate here on the Cumberland Grisdales. Because Grisdale is a place name, then the early people taking the name were most likely styled as such because they came from there and had most probably moved some way away. They would have been referred to, for example, as John or Richard of Grisdale (or in the Norman French version John or Richard de Grisdale), to distinguish them from other Johns and Richards living nearby. If people lived in the same place, say Grisdale itself, they’d be no need to say they were ‘of Grisdale’.

But let’s not forget the countless thousands of German civilians who died horrific deaths in cities all over Germany which were subjected to Allied fire-bombing and subsequent firestorms, as was Dortmund on this night of 22/23 May 1944.

But let’s not forget the countless thousands of German civilians who died horrific deaths in cities all over Germany which were subjected to Allied fire-bombing and subsequent firestorms, as was Dortmund on this night of 22/23 May 1944.

The reason I want to write about Joseph Lowe is not so much to do with the fact that he married a Grisdale girl, or even because he lived and walked in places called Grisedale (which didn’t have the E in the nineteenth century); rather he became a wonderful photographer of the Lake District in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The reason I want to write about Joseph Lowe is not so much to do with the fact that he married a Grisdale girl, or even because he lived and walked in places called Grisedale (which didn’t have the E in the nineteenth century); rather he became a wonderful photographer of the Lake District in the late 1800s and early 1900s.