Did a Cumbrian soldier “save England and Europe” from Napoleon?

In the mid-nineteenth century in the small Cumbrian market town of Penrith there was a public house called the ‘General Lefebvre’. Locals jokingly referred to it as the ‘General Grisdale’, after its publican, an old ex-Sergeant Major called Levi Grisdale. It seems that Levi was quite a character, and we might well imagine how on cold Cumbrian winter nights he would regale his quests with tales of his exploits as a Hussar during the Napoleonic Wars. How he had captured the French General Lefebvre in Spain, as the British army were retreating towards Corunna, or even telling of how it was he, at the Battle of Waterloo, who had led the Prussians onto the field; a decisive event that had turned the course of the battle and, it is usually argued, led to Napoleon’s final defeat.

Scouts of the 10th Hussars During the Peninsular War – W B Wollen 1905

Numerous individual stories survive from these wars, written by participants from all sides: French, British, German and Spanish. Yet a great number of these come from the ‘officer classes’. Levi was not an officer and, as far as is known, he never wrote his own story. Be that as it may, using a variety of sources (not just from the British side) plus some detailed research in the archives, undertaken by myself and others, it is possible to reconstruct something his life. Levi spent 22 years in the army, fought in 32 engagements, including at the Battle of Waterloo, rose to be a Sergeant Major and was highly decorated. There is even an anonymous essay in the Hussars’ Regimental museum entitled: How Trooper Grisdale, 10th Hussars, Saved England and Europe! This suggested, possibly with a degree of hyperbole, that it was Levi who caused Napoleon to leave the Spanish Peninsular in disgust! But the events of the Peninsular War were decisive. Many years later Napoleon wrote:

That unfortunate war destroyed me … all my disasters are bound up in that knot.

I greatly enjoyed discovering a little about Levi. What follows is my version of this Cumbrian’s life and deeds. I hope you will enjoy it too!

Levi Grisdale was born in 1783, near Penrith in Cumberland’s Lake District. He came from a long line of small yeomen farmers. His father, Solomon, and his grandfather, Jonathon, had both been farmers. They were born in the nearby small hill village of Matterdale; where the Grisdale family had lived for hundreds of years. Although obviously a country boy, Levi somehow found his way to London, where on 26th March 1803, aged just 20, he enlisted for “unlimited service” as a private or ‘trooper’ in the 10th Light Dragoons, later to become ‘Hussars’ – an elite British cavalry regiment. How and why he enlisted in the army we do not know. His older brother Thomas was probably already a soldier based at the cavalry barracks on the outskirts of Canterbury, and maybe this contributed to Levi’s decision. We know nothing of Levi’s first years in the army; but in October 1808 he, with the 10th Hussars, embarked at Portsmouth for Spain.

A Charge of the 10th Hussars under Lord Paget

The regiment, having passed through Corunna, joined up with the now retreating British army, under its Commander-in-Chief, Sir John Moore, at Zamora on December 9, 1808. Under Sir John Slade, they became part of the army’s defensive rear-guard. They arrived at Sahagun in Spain on the 21st December – just in time to take part in the tail end of a successful action known as the Battle of Sahagun. Before the battle, Levi had been made a ‘coverer’ – a sort of bodyguard or ‘minder’ – for the fourteen year old Earl George Augustus Frederick Fitz-Clarence. It wasn’t unusual for wealthy and well-connected young men to become British officers at such a tender age, and Fitz-Clarence was certainly well-connected. He was the bastard son of the future King William IV and nephew of the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV – who was the regiment’s Colonel-in-Chief.

During the battle Levi was wounded in the left ankle by a musket ball. It can’t have been too serious a wound because only a few days later he was to take part in another engagement. His exploits there were, in large part, responsible for us being able to reconstruct Levi’s story today. I will take some pains to explain what happened. The account I will present is based on numerous sources and on several eyewitness accounts; not just British, but also German, French and Spanish. There are some inconsistencies but when taken together they provide a coherent enough picture.

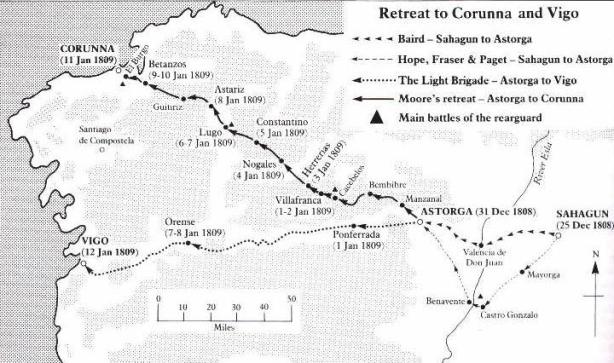

The British Retreat to Corunna 1808-1809

Despite the victory at Sahagun, the British army had continued its retreat towards Astorga and Corunna. But Napoleon had heard that the British were intent on a crossing of the River Esla, two miles from the Spanish town of Benavente. He sent his elite cavalry, the Chasseurs à cheval, commanded by one of his favourites, General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes, to cut them off and prevent the crossing. But due to dreadful weather they had been slowed down and they arrived just too late. Sir John Moore had already crossed the river on the 24th and departed with the bulk of the British army. He had, however, left a strong cavalry rearguard in the town of Benavente, and a small detachment was watching the river fords. Early on the morning of 29th December, British engineers destroyed the bridge at Castrogonzalo. When Lefebvre and his force of about 500 – 600 cavalry arrived, we are told that this was at nine in the morning, there seemed no way to cross, because the river “was swollen with rain.”

Lefebvre could see that “outlying pickets of the British cavalry were stationed along the Western bank of the River Esla.” He thought, wrongly as it turned out, that the few scouts to be seen were all that remained of the British at Benavente. Eventually he managed to find one place to ford the river and, according to one report, first sent across “a peasant mounted on a mare” to see find out what response there would be. Seeing there was none, Lefebvre crossed the river “with three strong squadrons of his Chasseurs and a small detachment of Mamelukes” – though not without great difficulty.

One account, drawing on a number of sources, nicely sums up what ensued:

The French forced the outlying pickets of the British cavalry back onto the inlaying picket commanded by Loftus Otway (18th Hussars). Otway charged, despite heavy odds, but was driven back for 2 miles towards the town of Benavente. In an area where their flanks were covered by walls, the British, now reinforced by a troop or squadron of the 3rd Hussars King’s German Legion, and commanded by Brigadier-General Stewart, counter-attacked and a confused mêlée ensued. The French, though temporarily driven back, had superior numbers and forced the British hussars to retreat once more, almost back to Benavente. Stewart knew he was drawing the French towards Paget and substantial numbers of British reserves. The French had gained the upper hand in the fight and were preparing to deliver a final charge when Lord Paget made a decisive intervention. He led the 10th Hussars with squadrons of the 18th in support, around the southern outskirts of Benavente. Paget managed to conceal his squadrons from French view until he could fall on their left flank. The British swords, often dulled by their iron scabbards, were very sharp on this occasion. An eyewitness stated that he saw the arms of French troopers cut off cleanly “like Berlin sausages.” Other French soldiers were killed by blows to the head, blows which divided the head down to the chin.

The French fought their way back to the River Esla and started to cross to its eastern bank – swimming with their horses. But many were caught by the pursuing British cavalry, and either killed or made prisoner. General Lefebvre, however, did not escape. His horse had been wounded and when it entered the river it refused to cross. He and some of his men were surrounded by the British cavalry under Lord Paget, which consisted of the 18th Hussars and half of the 3rd Hussars, King’s German Legion. During this encounter Lefebvre was wounded and taken prisoner, along with about seventy of his Chasseurs.

General Lefebvre is Captured at Benaventa. Painting by Dennis Dighton. Royal Collection, Windsor

So who was it that captured General Lefebvre? Some British sources claim simply that it was Private Grisdale. In Levi’s own regimental book we read that Lefebvre was pursued by the “Hussars” and “refusing to stop when overtaken, was cut across the head and made prisoner by Private Levi Grisdall (sic).” Other witnesses suggest that it was in fact a German 3rd Hussar, called Private Johann Bergmann, who captured the General, and that it was he who subsequently handed over his captive to Grisdale.

Any continuing mystery, however, seems to be cleared away by later witness statements made by Private Bergmann himself. His statement is corroborated by several other German Hussars who had taken part in the action, and by letters written by some German officers who were also present. Bergmann’s extensive testimony, taken at Osterholz in 1830 , is recorded in the third person. It states that there were:

three charges that day… at the third charge, or in reality the pursuit, he came upon the officer whom he made prisoner. He was one of the first in the pursuit, and as he came up with this officer, who rode close in the rear of the enemy, the officer made a thrust at him with a long straight sword. After, however, he had parried the thrust, the officer called out ‘pardon.’ He did not trouble himself further about the man, but continued the pursuit; an English Hussar, however, who had come up to the officer at the same time with him, led the officer back.

Bergmann went on to say that he hadn’t known that the officer was Lefebvre until after the action, when he was told he should “have held fast the man.” He added that he was young and “did not trouble” himself about the matter. All he remembered was that the officer “wore a dark green frock, a hat with a feather, and a long straight sword.”

All the other German witnesses and letters confirm Bergmann’s story, but we also learn that the General had fired a pistol at Bergmann “which failing in its aim, he offered him his sword and made known his wish to be taken to General Stewart.” But Bergmann “didn’t know General Stewart personally, and while he was enquiring where the general was to be found, a Hussar of the tenth English joined him, and led away the prisoner.”

So this it seems is the truth of the matter: Lefebvre was surrounded by a German troop and captured by Private Johann Bergmann. Levi Grisdale, with the 10th Hussars, might have arrived at the scene at the same time as Bergmann or very slightly after, opinions differ. Lefebvre asked to be taken to General Stewart and so Bergmann, “not knowing General Stewart personally”, handed him over to Private Grisdale who “led the prisoner away.”

Lefebvre was delivered to the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John Moore. Moore, who, we are told, treated the General, who had suffered a superficial head wound, “kindly” and “entertained him at his table.” He also gave him his own sword to replace the one taken when he surrendered. “Speaking to him in French”, General Moore, “provided some of his own clothes; for Lefebvre was drenched and bleeding.” He then “sent a message to the French, requesting Lefebvre’s baggage, which was promptly sent.”

Napoleon, who had viewed the action from a height overlooking the river, didn’t seem too put out by the losses of what he called his “Cherished Children.” But he was very upset when he heard of Lefebvre’s capture. He wrote to Josephine (my translation):

Lefebvre has been taken. He made a skirmish for me with 300 Chasseurs; these show-offs crossed the river by swimming, and threw themselves into the middle of the English cavalry. They killed many of them; but, returning, Lefebvre’s horse was wounded: he was drowning; the current led him to the bank where the English were; he has been taken. Console his wife.

In the aftermath of the battle, a Spanish report from the town of Benavente itself, tells us that on:

The night of the 29th they (the British) used the striking pines growing on the high ground behind the hospitals as lights, at every step coming under the fire of French artillery from the other side of the river, answered feebly by the English, whose force disappeared totally by the morning, to be replaced by a dreadful silence and solitude….

The British cavalry had slipped away and, with the rest of the army, continued its horrendous winter retreat to Corunna. Levi Grisdale and the 10th Hussars were with them.

General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes

General Lefebvre himself was later sent as a prisoner to England, and housed at Cheltenham where he lived for three years. As was the custom, he gave his word or “parole” as a French officer and gentleman that he would not try to escape. He was even allowed to be joined by his wife Stephanie. It seems that the couple: “were in demand socially and attended social events around the district.” Other reports tell us that General Lefebvre was in possession of a “fine signet ring of considerable value which had been given him years earlier by his Emperor Napoleon. Lefebvre used this ring as a bribe to get escape and was thus able to escape back to France, where he rejoined his Division.” This was, says one commentator, “an unpardonable sin according to English public opinion.” So much for a gentleman’s word! The Emperor reinstated him as commander of the Chasseurs and he would go on to fight in all Napoleon’s subsequent campaigns, right up to Waterloo – where he would share the field once again with Levi Grisdale.

I have kept us a little too long in Spain. This is, after all, not the story of the retreat to Corunna, much less a history of the first Spanish chapter of the Peninsular War. After the so-called March of Death and the Battle of Corunna, Levi Grisdale was evacuated back to England by the Royal Navy – with what was left of the 10th Hussars. Here his fame started to spread. The Hampshire Telegraph of 18th February 1809 announced that Grisdale was back in Brighton with his regiment and described him as: “tall, well-made, well looking, ruddy and expressive.” He was promoted to Corporal and awarded a special silver medal by the regiment, which was inscribed:

Corporal Grisdale greatly distinguished himself on the 1st day of January 1809 (sic). This is adjudged to him by officers of the regiment.

The years passed. The regiment moved from Brighton to Romford in Essex, but was once again back in Brighton in 1812. Of this time we know little; only a few events in Levi’s life. Soon after his arrival back in England, he somehow arranged to get away to Bath, where on 29 March 1809, he married Ann Robinson in St James’ Church. Their only son, also called Levi, was born and baptized at Arundel on 12 March 1811 – sadly he was to die young. On 17 February 1813, he “was found guilty of being drunk and absent from barracks.” But, it seems, he was neither reduced to the ranks nor flogged. Other evidence suggests that the whole regiment was “undisciplined and tended to drunkenness.” Whether the leniency of his treatment was due to his record at Benavente we will probably never know.

But by February 1813, Levi, by this time a Sergeant, was back in the Iberian Peninsula, serving in a coalition army under Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, who was later to become the Duke of Wellington. With the 10th Hussars, he fought his way through Portugal, Spain and France and, so his regiment’s records tell us, was actively engaged at the Battles of Morales, Vitoria, Orthes and, finally, at the Battle of Toulouse in April 1814. Here the British and their allies were badly mauled. But news soon reached the French Marshall Soult that Napoleon had abdicated and Soult agreed to an armistice.

It is said that Levi Grisdale led Bluecher’s Prussians onto the field at Waterloo

And that should really have been that as far as Levi Grisdale’s military campaigning days was concerned. Yet one more chapter lay ahead. A chapter that would no doubt later provide Levi with another great story to tell in his Penrith public house. Napoleon, we might recall, was to escape from his exile on the Island of Elba in February 1815. He retook the leadership of France, regathered his army, and was only definitively defeated at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815. It has often been said that the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo “hung in the balance” until the arrival of the Prussian army under Prince von Blücher. One writer puts it thus:

Blücher’s army intervened with decisive and crushing effect, his vanguard drawing off Napoleon’s badly needed reserves, and his main body being instrumental in crushing French resistance. This victory led the way to a decisive victory through the relentless pursuit of the French by the Prussians.

And here it is that we last hear of Levi’s active military exploits. According to his obituary, published in the Cumberland and Westmoreland Advertiser on 20 November 1855, Levi had been posted on the road where the Prussians were expected to arrive, and he led them onto the field of battle! We are also told that during the battle “his horse was shot from under him and he was wounded in the right calf by a splinter from a shell.” Finally, according to a letter written by Captain Thomas Taylor of the 10th Hussars, written to General Sir Vivian Hussey in 1829, Levi, who was a by now a Sergeant in No1 troop under Captain John Gurwood, and “who was one of the captors of Lefebvre … conducted the vedettes in withdrawing from French cavalry during the battle.

Of course, Levi Grisdale certainly did not “save England and Europe” from Napoleon. But, along with thousands of other common soldiers, he played his part and, unlike countless others on all sides, he survived to tell his tales in his pub.

What became of Levi? After he returned to England, he was promoted to Sergeant Major and remained another nine years with the 10th Hussars. When he left the army in 1825, aged only 42 but with twenty-two years of active service and thirty-two engagements behind him, his discharge papers said that he was suffering from chronic rheumatism and was “worn out by service.” Hardly surprising we might think. The army gave him a pension of 1s 10d a day. His papers also state that his intended place of residence was Bristol. He was as good as his word as and he was to become the landlord of the Stag and Star public house in Barr Street, Bristol.

Christ Church, Penrith – where Levi Grisdale is buried

Yet by 1832 Levi and his family had moved back to his native Penrith. His wife Ann died there in July of that year. It seems that Levi was not one to mourn for too long. Within about two weeks he had married again. This time a woman called Mary Western – with whom he had four children. He continued his life as a publican and, as I have mentioned, christened his pub the General Lefebvre; he even hung a large picture of the General over the entrance. During his last years, Levi Grisdale gave up his pub and worked as a gardener. He died of ‘dropsy’ on 17 November 1855 in Penrith, aged 72, his occupation being given as “Chelsea pensioner.” He was buried in the graveyard of Christ Church in Penrith.

Despite what we know about Levi’s life, we will never know what was most important to him – his family, his comrades? Nor will we know what he thought of the ruling ‘officer class’? What he thought of the social and political system that had led him to fight so many battles against adversaries he knew little about? Nor whose side he was really on? We will never know these things, though we can imagine!

As General Macarthur once said, “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” ‘General’ Levi Grisdale certainly died but, thankfully, his memory has not yet faded away.

Sources

Mary Grisdale. Levi Grisdale. Unpublished research 2006; David Fallowfield. Levi Grisdale 1783-1855, Unpublished article. Penrith; Philip J. Haythornthwaite. Corunna 1809: Sir John Moore’s Fighting Retreat. London: Osprey Publishing 2001; Lettres de Napoléon à Joséphine, Tome Second, Paris 1833, Firman Didot Freres; Christopher Hibbert. Corunna, Batsford 1961; Michael Clover. The Peninsular War 1807-1814. Penguin Books 2003; North Ludlow Beamish. History of the King’s German Legion, Harvard 1832; Christopher Summerville. The March of Death: Sir John Moore’s Retreat to Corunna. Greenhill books 2006; Brime, D. Fernando Fernandez. Historical Notes of the Town of Benavente and its Environs. Valladolid 1881; Wikipedia. Battle of Benavente. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Benavente.; The Museum of the King’s Royal Hussars. http://www.horsepowermuseum.co.uk/index.html .