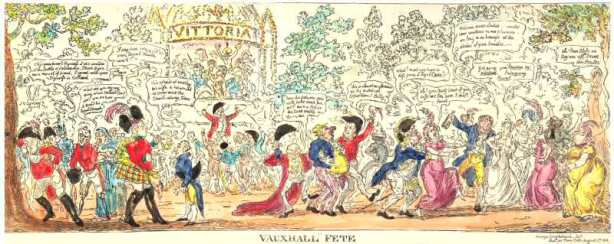

I have wondered for some time what several members of one Grisdale family were doing in Arundel in Sussex in the early 1800s. How had they come to be there? The first son of the heroic Hussar Levi Grisdale, who fought in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo, was born in Arundel in 1811 – he too was called Levi. Levi’s sister Jane married Arundel stonemason John Booker in Arundel and their first five children were born there between 1808 and 1814. One of these children, William Booker, was an early emigrant to New Zealand. And then there is Levi and Jane’s older brother Joseph who had three children in Arundel between 1806 and 1811. It is Joseph who provides the original connection with Arundel, through his relationship with Charles Howard, the 11th Duke of Norfolk.

In general I don’t have any time for Britain’s landed aristocrats. For centuries they were the repressors and exploiters of the people of the island. The Howard family, whose wealth went back at least to the 1300s, were and still are the premier Catholic aristocratic family in the realm. As Dukes of Norfolk they rank first (below the royal family) in the Peerage of England. Many of the Howard dukes of Norfolk were executed for treason and some of the family even married kings, such as Henry VIII’s wife Catherine Howard.

Arundel Castle

The families main seat was and still is Arundel Castle in Sussex, but they had lands all over the country: in Holme Lacy in Herefordshire for example and, importantly for the Grisdales, the Howards had, in a roundabout way, become the barons of Greystoke in Cumberland in the late sixteenth century; and of course Matterdale is part of this barony.

Greystoke Castle,Cumberland

Charles Howard was born in 1746 and became the 11th Duke of Norfolk in 1786. He was first educated by the Catholic priests in Greystoke Castle, where he spent the early years of his life, before being sent to Douai in France for more Catholic teaching. He would later convert to Protestantism for reasons of political expediency. It was no doubt at Greystoke Castle that a young Joseph Grisdale first entered into the Howard family service. Joseph was born in Matterdale in 1769 the son of farmer Solomon Grisdale. The family then moved to Greystoke where Levi was born in 1783.

Solomon Grisdale was a tenant of Charles Howard’s father, the 10th duke of Norfolk, also called Charles. I would imagine that it was sometime in the mid 1780s that Joseph Grisdale entered into service with the Howards at Greystoke Castle, perhaps initially as a footman or something similar. Whatever the case, by 1794 Joseph had moved to London with the new duke and was in his service at the duke’s palatial London residence in St James’s Square called Norfolk House. Joseph married another servant (maybe of the duke) called Martha Broughton in St George’s church in Hanover Square on 6 June 1794 – both were said to be servants living in the parish of St James.

St James’s Square with Norfolk House on the right

As a servant of the duke Joseph would have travelled around a lot because even in old age he was continually on the move between his various estates. It is likely that buy the time of his marriage Joseph had already moved up the pecking order in the below-stairs hierarchy; maybe he was the duke’s personal valet or maybe, perhaps later, he even became butler – the top of the tree. Given what I will tell later he must have been one or the other. Certainly Joseph would have accompanied the duke during his stays at the ducal seat of Arundel Castle, also to Holme Lacy where the duke’s deranged wife was incarcerated until her death in 1820, and certainly to Greystoke Castle in Cumberland, near where Joseph’s family still lived.

Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel

By the early 1800s at the latest it seems that Joseph and Martha had their ‘home’ at Arundel. Maybe this was a cottage in the castle’s grounds or perhaps even in the castle itself. It was in Arundel that their three children were born: Mary in 1806, Thomas in 1808 and John in 1811. It’s interesting to note that at least Thomas and John were baptized in the Roman Catholic Fitzalan Chapel in the grounds of Arundel Castle. Actually the Fitzalan Chapel, the private chapel of the dukes of Norfolk, many of whom are buried there, is only a part of the Church of England Arundel parish church of St Nicholas

This charming little church (St Nicholas) beside Arundel Castle and opposite Arundel Cathedral is the local Church of England parish church and dates back to 1380…

A peculiarity of the church is that part of the building is the Fitzalan Chapel which is a Catholic chapel in Arundel Castle’s grounds where the Dukes of Norfolk and Earls of Arundel are buried. This catholic chapel is separated from the protestant parish church by just a glass screen and it is possible to peer from one to the other.

The duke, Charles Howard, had converted to Protestantism in 1780 in order to get into Parliament as an MP, but ‘remained a Catholic at heart’ as everyone knew. So had the duke’s servant Joseph Grisdale converted to Catholicism or, perhaps more likely, his wife Martha was a Catholic?

The Prince of Wales (later King George the fourth). Levi’s admirer and a drinking buddy of Charles Howard, the Duke of Norfolk

Before I tell more of Joseph and the duke let’s try to imagine what led his brother and sister, Levi and Jane, to Arundel as well. When Hussar Levi’s first son Levi was baptized in Arundel in 1811 his brother Joseph was, as we will see, a very valued servant of the duke. Levi was still in the army but at the height of his fame. After he had captured Napoleon’s favourite general Lefebvre in Spain in late 1808, his regiment’s Colonel-in- Chief the Prince of Wales, later King George IV, insisted he was promoted to Corporal saying this would be the first of many promotions – Levi ended up a Sergeant Major. In fact the Prince of Wales had offered to pay for an education for Levi but he had refused this. So maybe Levi and his wife were just visiting brother Joseph at Arundel when their son was born or, just possibly, Levi’s wife Ann was living in Arundel while Levi moved around with his regiment? Regarding sister Jane, I can see no other explanation but that Joseph had got her a job as a servant in the duke’s household at Arundel and while working there she married local mason John Booker in 1805.

It’s not just that Joseph Grisdale was a servant of the duke of Norfolk but it seems he was his favourite and most trusted servant. When the duke died in 1815 at his London residence of Norfolk House he of course left a will. As he didn’t have any children most of the will concerns to whom all his extensive properties should go to; including of course Greystoke in Cumberland. I won’t go into all the details here, but the duke willed that his servants should each receive three years wages, quite a generous gesture. But he singled out just one servant, Joseph Grisdale, to whom he bequeathed on top of three years wages the extremely large sum (for the time) of £300!

When you read below the type of life the duke led and what his servants had to do for him you might like to think as I do, that Joseph Grisdale must have been very close to the duke during his drunken and debauched life – possibly as I have suggested being his personal valet (‘minder’ even), rather than his butler (or one of his butlers).

So what sort of man was Charles Howard, the 11th duke of Norfolk? What had Joseph had to deal with? We might get an idea from the Posthumous Memoirs of My Own Time of Sir N W Wraxall, published in 1836. I’ll quote a length because it gives an idea of England’s aristocratic rulers in the glorious Georgian age. Note that Howard was Lord Surrey before he became duke.

At a time when men of every description wore hair-powder and a queue, he had the courage to cut his hair short, and to renounce powder, which he never used except when going to court. In the session of 1785, he proposed to Pitt to lay a tax on the use of hair-powder, as a substitute for one of the minister’s projected taxes on female servants. This hint, though not improved at the time, was adopted by him some years afterwards. Pitt, in reply to Lord Surrey, observed, that ‘the noble lord, from his rank, and the office which he held (deputy earl-marshal of England), might dispense, as he did, with powder; but there were many individuals whose situation compelled them to go powdered. Indeed, few gentlemen permitted their servants to appear before them unpowdered.’

Courtenay, a man who despised all aid of dress, in the course of the same debate remarked, that he was very disinterested in his opposition to the tax on maid-servants; ‘for’ added he, ‘as I have seven children, the ‘jus septem liberorum’ will exempt me from paying it; and I shall be as little affected by the tax on hair-powder, if it should take place as the noble lord who proposed it’.

“A natural crop – alias a Norfolk dumpling” showing the Duke of Norfolk. It was drawn by James Gillray and published in 1791

Strong natural sense supplied in Lord Surrey the neglect of education; and he displayed a sort of rude eloquence, whenever he rose to address the house, analogous to his formation of mind and body. In his youth, — for at the time of which I speak he had attained his thirty-eighth year, — he led a most licentious life, having frequently passed the whole night in excesses of every kind, and even lain down, when intoxicated, occasionally to sleep in the streets, or on a block of wood. At the ‘Beef-steak Club,’ where I have dined with him, he seemed to be in his proper element. But few individuals of that society could sustain a contest with such an antagonist, when the cloth was removed. In cleanliness be was negligent to so great a degree, that he rarely made use of water for purposes of bodily refreshment and comfort. He even carried the neglect of his person so far, that his servants were accustomed to avail themselves of his fits of intoxication, for the purposes of washing him. On those occasions, being wholly insensible to all that passed about him, they stripped him as they would have done a corpse, and performed on his body the necessary ablutions. Nor did he change his linen more frequently than he washed himself. Complaining one day to Dudley North that he was a martyr to the rheumatism, and had ineffectually tried every remedy for its relief, ‘Pray, my lord,’ said he, ‘did you ever try a dean shirt?’

Drunkenness was in him an hereditary vice, transmitted down, probably, by his ancestors from the Plantagenet times, and inherent in his formation. His father, the Duke of Norfolk, indulged equally in it; but he did not manifest the same capacities as the son, in resisting the effects of wine. It is a fact that Lord Surrey, after laying his father and all the guests under the table at the Thatched House tavern in St Jameses street, has left the room, repaired to another festive party in the vicinity, and there recommenced the unfinished convivial rites; realizing Thompson’s description of the parson in his ‘ Autumn,’ who, after the foxchase, survives his company in the celebration of these orgies:

‘Perhaps some doctor of tremendous paunch.

Awful and vast, a black abyss of drink.

Outlives them all; and from his buried flock.

Returning late with rumination sad.

Laments the weakness of these latter times.’

Even in the House of Commons he was not always sober; but he never attempted, like Lord Galway, to mix in the debate on those occasions. No man, when master of himself, was more communicative, accessible, and free from any shadow of pride. Intoxication rendered him quarrelsome; though, as appeared in the course of more than one transaction he did not manifest Lord Lonsdale’s troublesome superabundance of courage after he had given offence. When under the dominion of wine, he has asserted that three as good Catholics sat in Lord North’s last parliament as ever existed; namely, Lord Nugent, Sir Thomas Gascoyne and himself. There might be truth in this declaration. Doubts were, indeed, always thrown on the sincerity of his own renunciation of the errors of the Romish church; which aet was attributed more to ambition and the desire of performing a part in public life, or to irreligion, than to conviction. His very dress, which was most singular, and always the same, except when he went to St. James’s, namely, a plain blue coat of a peculiar dye, approaching to purple, was said to be imposed on him by his priest or confessor as a penance. The late Earl of Sandwich so assured me; but I always believed Lord Surrey to possess a mind superior to the terrors of superstition. Though twice married while a very young man, he left no issue by either of his wives. The second still survives, in a state of disordered intellect, residing at Holme Lacy in the county of Hereford.

John Howard, the first Howard Duke of Norfolk, fell with Richard the Third at Bosworth in 1485

As long ago as the spring of 1781, breakfasting with him at the Cocoa-tree coffee-house, Lord Surrey assured me that he had proposed to give an entertainment when the year 1783 should arrive, in order to commemorate the period when the dukedom would have remained three hundred years in their house, since its creation by Richard the Third. He added, that it was his intention to invite all the individuals of both sexes whom he could ascertain to be lineally descended from the body the Jockey of Norfolk, the first duke of that name, killed at Bosworth Field. ‘But having already,’ said he, ‘discovered nearly six thousand persons sprung from him’, a great number of whom are in very obscure or indigent circumstances, and believing, as I do, that as many more may be in existence, I have abandoned the design.’

Fox could not boast of a more devoted supporter than Lord Surrey, nor did his attachment diminish with his augmentation of honours. On the contrary, after he became Duke of Norfolk he manifested the strongest proofs of adherence; some of which, however, tended to injure him in the estimation of all moderate men. His conduct in toasting ‘The sovereign majesty of the people,’ at a meeting of the Whigs, held in February, 1798, at the Crown and Anchor tavern, was generally disapproved and censured. Assuredly it was not in the ‘Bill of Rights,’ nor in the principles on which reposes the revolution of 1688, that the duke could discover any mention of such an attribute of the people. Their liberties and franchises are there enumerated; but their majesty was neither recognised nor imagined by those persons who were foremost in expelling James the Second. The observations with which his grace accompanied the toast, relative to the two thousand persons who, under General Washington, first procured reform and liberty for the thirteen American colonies, were equally pernicious in themselves and seditious in their tendency. Such testimonies of approbation seemed, indeed, to be not very remote from treason.

The Duke of York escapes from the French in Flanders in 1794

The duke himself appeared conscious that he had advanced beyond the limits of prudence, if not beyond the duties imposed by his allegiance; for, a day or two afterwards, having heard that his behaviour had excited much indignation at St James’s, he waited on the Duke of York, in order to explain and excuse the proceeding. When, he had so done, he concluded by requesting, as a proof of his loyalty, that, in case of invasion, his regiment of militia (the West Riding of Yorkshire, which he commanded) might be assigned the post of danger. His royal highness listened to him with apparent attention; assured him that his request should be laid before the king; and then breaking off the conversation abruptly, ‘Apropos, my lord,’ said he, ‘ have you seen “Blue Beard?” This musical pantomime entertainment, which had just made its appearance at Drury-lane theatre, was at that time much admired. Only two days subsequent to the above interview, the Duke of Norfolk received his dismission both from the lord-lieutenancy and from his regiment.

Lord Liverpool – Prime Minister

As he advanced in age he increased in bulk; and the last time that I saw him, (which happened to be at the levee at Carlton House, when I had some conversation with him,) not more than a year before his decease, such was his size and breadth, that he seemed incapable of passing through a door of ordinary dimensions. Yet he had neither lost the activity of his mind nor that of his body. Regardless of seasons, or impediments of any kind, he traversed the kingdom in all directions, from Greystock in Cumberland, to Holme Lacy and Arundel Castle, with the rapidity of a young man. Indeed, though of enormous proportions, he had not a projecting belly, as Ptolemy Physcon is depictured in antiquity ; or like the late king of Wirtemberg, who resembled in his person our popular ideas of Punch and might have asserted with Falstaff, that ‘he was unable to get sight of his own knee.’ In the deliberations of the house of peers, the Duke of Norfolk maintained the manly independence of his character, and frequently spoke with ability as well as with information. His talents were neither impaired by years nor obscured by the bacchanalian festivities of Norfolk House, which continued to the latest period of his life; but he became somnolent and lethargic before his decease. On the formation of Lord Liverpool’s administration in 1812, he might unquestionably have received ‘the Garter,’ which the Regent tendered him, if he would have sanctioned and supported that ministerial arrangement. The tenacity of his political principles made him, however, superior to the temptation. His death has left a blank in the upper house of parliament.

It’s not for nothing that Charles Howard was referred to as the ‘Drunken Duke’. One can examine what Joseph Grisdale had had to deal with over the years and perhaps why the duke was so generous to Joseph in his will.

The Crown and Anchor

Yet there was more than this to the duke. Much as I approve of any vilification of England’s debauched, indolent and useless landed aristocracy, I think Charles Howard had one great redeeming quality: in his drunken state he still cared a little about the people. As Wraxall’s writings make clear, Howard had been deprived of some of his offices by King George III for his speech to mark the birthday of the Whig politician Charles James Fox held at the Crown and Anchor on Arundel Street in St. James’, London (yes, named after the seat of the dukes of Norfolk) in early 1798.

The Crown and Anchor tavern was one of the major landmarks of late-Hanoverian London. In the period of popular political discontent which stretched from the 1790s through to the Chartist movement of the 1840s, the tavern’s name became so closely associated with anti-establishmentarian politics that the term ‘Crown and Anchor’ became synonymous with radical political beliefs…

The term ‘tavern’ conjures up images of a typically snug English pub; however this would a wholly inaccurate means of describing the Crown and Anchor. Following extensive refurbishment in the late 1780s the tavern stood at four stories in height and stretched an entire city block from Arundel Street to Milford Lane.

The meeting to celebrate Fox’s birthday was attended by upwards of 2,000 people. The Duke of Norfolk was there, probably with Joseph Grisdale in attendance to look after the drunken duke.

The festivities were an annual event, and 1798 saw one of the largest assemblies ever held at the tavern. The Duke’s penchant for drinking and revelry was renowned in London society, as were his liberal political views, despite his close friendship with the Prince Regent. At the request of the chair of the occasion, the Duke of Bedford, the Duke of Norfolk proposed a string of toasts to the 2000-strong audience. Though convention stipulated the first toast at such a public occasion be offered as a salutation to the Monarch, the Duke raised his glass and gave instead to ‘the rights of the people’. The flagrant disregard of custom and etiquette met a mix of cheers and murmured disgruntlement. When the room quieted, the Duke continued with an altogether scandalous line-up of toasts bordering on the treasonous: ‘to constitutional redress for the wrongs of the people’; to ‘a speedy and effectual reform in the representation of the people in parliament’; to ‘the genuine principles of the British Constitution’; and to ‘the people of Ireland—may they be speedily restored to blessings of law and liberty’. When he finally offered a toast to the King, it contained a thinly disguised rebuke reminding the Monarch of his duty—to ‘Our Sovereign’s health—the majesty of the people’.

‘The establishment’s reaction to Norfolk’s speech was captured in Gillray’s The Loyal Toast – As Norfolk salutes the majesty of the people a list of his various offices and titles is being shredded behind him. The Duke was dismissed from all his official positions, including his position on the Privy Council and the Lord Lieutenancy of the West Riding. Signalling that the Duke’s powerful friendships would not protect him, the notification of dismissal was sent during a dinner with the Prince Regent. Despite eventually satisfying the King with proclamations of loyalty, he was not reinstated to his official post until 1807.’

Gillray’s The Loyal Toast

What became of faithful Joseph Grisdale after the Duke of Norfolk’s death in 1815? It seems that Joseph used some or all of the money the duke had left him to buy two houses, one at Ockley in Surrey and one at in Rudgwick in Sussex, both on lands in the estates of the dukes of Norfolk. In 1822 Joseph is living at his house in Ockley but then rents it out until 1830. The house in Rudgwick was rented out by Joseph in 1820, but by 1833 Joseph’s daughter Mary married George Field in Rudgwick church, so maybe Joseph was living there by then having retired from his years of service? As yet I can’t be sure when and where Joseph and Martha died. His children went on to other things – but some still with connections with the dukes of Norfolk – I’ll return to them at a later date.

Old Rudgwick