In the 1830s Vauxhall Gardens had been one of London’s ‘pleasure gardens’ since the mid seventeenth century. It ‘drew all manner of men and supported enormous crowds, with its paths being noted for romantic assignations. Tightrope walkers, hot air balloon ascents, concerts and fireworks provided amusement.’ Our story here concerns one such balloon flight and one parachute descent and how a young Thomas Grisdale became involved.

A satirical illustration by Cruikshank entitled ‘Vauxhall Fete’ celebrating the achievements of Wellington.

In the late 1700s James Boswell wrote:

Vauxhall Gardens is peculiarly adapted to the taste of the English nation; there being a mixture of curious show, — gay exhibition, musick, vocal and instrumental, not too refined for the general ear; — for all of which only a shilling is paid; and, though last, not least, good eating and drinking for those who choose to purchase that regale.

Later, in 1836, Charles Dickens wrote in Sketches by Boz:

Vauxhall Gardens

We paid our shilling at the gate, and then we saw for the first time, that the entrance, if there had been any magic about it at all, was now decidedly disenchanted, being, in fact, nothing more nor less than a combination of very roughly-painted boards and sawdust. We glanced at the orchestra and supper-room as we hurried past—we just recognised them, and that was all. We bent our steps to the firework-ground; there, at least, we should not be disappointed. We reached it, and stood rooted to the spot with mortification and astonishment. That the Moorish tower—that wooden shed with a door in the centre, and daubs of crimson and yellow all round, like a gigantic watch-case! That the place where night after night we had beheld the undaunted Mr. Blackmore make his terrific ascent, surrounded by flames of fire, and peals of artillery, and where the white garments of Madame Somebody (we forget even her name now), who nobly devoted her life to the manufacture of fireworks, had so often been seen fluttering in the wind, as she called up a red, blue, or party-coloured light to illumine her temple!

And then:

the balloons went up, and the aerial travellers stood up, and the crowd outside roared with delight, and the two gentlemen who had never ascended before tried to wave their flags as if they were not nervous, but held on very fast all the while; and the balloons were wafted gently away…

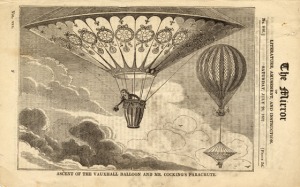

First balloon flight from Vauxhall Gardens by Charles Green in 1836

Always wanting the latest attraction and spectacle the Gardens featured the first balloon ascent from there in 1836. The proprietors asked the famous English balloonist Charles Green to build a new balloon for them; it was first called the Royal Vauxhall and then the Nassau. Green made a first successful flight from Vauxhall Gardens on 9 September 1836 ‘in company with eight persons… remaining in the air about one hour and a half’. On the 21 September ‘he made a second ascent, accompanied by eleven persons, and descended at Beckenham in Kent’. Further flights followed, including on 7 November, when with two others he crossed the channel and ‘descended the next day, at 7 a.m., at Weilburg in Nassau, Germany, having travelled altogether about five hundred miles in eighteen hours’. A feat that was much celebrated.

Charles Green’s balloon on the way to Germany in 1836

While successful balloon flights were becoming more common, parachute descents were still rare and highly dangerous. The first parachute jump had been made in France in 1785. In England André-Jacques Garnerin made the first parachute jump in 1802 which a professional watercolour artist called Robert Cocking had witnessed. He was inspired to develop a better design which wouldn’t sway from side to side during the descent as Garnerin’s umbrella-shaped parachute had done.

Cocking’s parachute

His design was based on the theory that an inverted cone-shaped parachute would be more stable. After many years perfecting his design which ‘engrossed very nearly all his attention’, he was ready and persuaded balloonist Charles Green first to let him accompany him on his first balloon flight from Vauxhall Gardens in 1836, and then, in July 1837, to stage a balloon flight with Cocking’s parachute attached underneath, from where he would release when sufficient height had been gained. The event was to be the main attraction of a Grand Day Fete at Vauxhall Gardens on 24 July 1837.

And so at 7.35 on that morning with thousands watched the sixty-one year-old Cocking ‘ascended hanging below the balloon, which was piloted by Green and Spencer’.

As the great balloon rises, his plan is to get up to at least 8000 feet before releasing himself. However, the weight of his apparatus slows the balloon’s ascent. The balloonists, Spencer and Green, jettison much of their ballast in a bid to rise higher. The balloon drifts over South London where it vanishes into a bank of clouds making it unsafe to drop any more ballast for fear of what’s below. Finally, over Greenwich and only a mile up, the balloonists advise Cocking they can get no higher. From his basket, Cocking yells, “Well, now I think I shall leave you. Good night, Spencer. Good night, Green.” With that, he severs the tether.

Mr. Green and Mr. Spencer, who were in the ‘car’ of the balloon, had… a narrow escape.

The Nassau lifts off with Cocking’s parachute in 1837

At the moment the parachute was disengaged they crouched down in the car, and Mr. Green clung to the valve-line, to permit the escape of the gas. The balloon shot upwards, plunging and rolling, and the gas pouring both the upper and lower valves, but chiefly from the latter, as the great resistance of the air checked its egress from the former. Mr. Green and Mr. Spencer applied their mouths to tubes communicating with an air bag with which they had had the foresight to provide themselves; otherwise they would certainly have been suffocated by the gas. Notwithstanding his precaution, however, the gas almost totally deprived them of sight for four or five minutes. When they came to themselves they found they were at a height of about four miles, and descending rapidly. They effected, however, a safe descent near Maidstone.

‘A large crowd had gathered to witness the event, but it was immediately obvious that Cocking was in trouble. He had neglected to include the weight of the parachute itself in his calculations and as a result the descent was far too quick. Though rapid, the descent continued evenly for a few seconds, but then the entire apparatus turned inside out and plunged downwards with increasing speed. The parachute broke up before it hit the ground and at about 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 m) off the ground the basket detached from the remains of the canopy. Cocking was killed instantly in the crash; his body was found in a field in Lee.’

Actually Cocking wasn’t instantly killed:

The balloon, freed of the weight, shot up like a skyrocket. Sadly, Cocking goes the other direction at much the same pace. In Norwood, a man described the chute’s descent as like a stone through a vacuum. With a tremendous crash, Cocking’s basket and chute slam into the ground at a farm near Lee. A shepherd is first to reach him. Cocking has been spilled from the basket, his head badly cut, his wig tossed some distance away. A few groans are the only brief sign of life. Carried by cart to the Tiger’s Head Inn, Cocking soon died of his injuries.

Cocking’s ascent and descent

Well that’s the story of Robert Cocking’s death, the first death by parachuting. The accident was of course widely reported in the press with many witness accounts and the testimony given at the inquest at the Tiger’s Head Inn in Lee.

‘In 1815 cavalry and foot regiments passed through Lee Green on their way to the Battle of Waterloo.’ Was Levi Grisdale with them?

In the early 19th century bare knuckle boxing matches took place at the Old Tiger’s Head. Horse racing and (human) foot racing take place in the 1840s but the police put a stop to these events, probably under pressure from local citizens.

As stated earlier, the first to reach Cocking, who was still alive, was John Chamberlain, a shepherd in the employ of Mr Richard Norman. the proprietor of Burnt Ash Farm (a place that has now disappeared under the suburban sprawl of south London). Chamberlain told the inquest how he had seen the ‘machine’ part from the balloon and it made a sound ‘like thunder’ which frightened his sheep. The ‘machine’ fell to the ground and turned over and was ‘broken to pieces’. He ran to the crash and the man (Cocking) was in the basket ‘up to his chest’ with his head lying on the ground’. The sight ‘quite turned him’. Others then arrived followed by his master Mr. Norman. He then heard a groan from Cocking.

One of the others who soon joined Chamberlain was Thomas Grisdale, Mr Norman’s footman.

Thomas Grisdale, footman to Mr Norman, of Burnt Ash Park, saw the parachute part from the balloon; it appeared to turn over and over; there was a great crackling; it appeared all to come down together; it was all closed up, not expanded; witness assisted: in taking the deceased out of the basket to do which they had to unfasten some ropes which were about him; he was laid on the grass; he breathed and appeared to live for two minutes or so; no ropes were attached to the deceased, but they had to remove the ropes attached to the basket, to get him out.

Fitzalan Chapel in Arundel where Thomas Grisdale was baptized

For anybody who is interested in who Mr Norman’s footman Thomas Grisdale was, well he was the son of the Joseph Grisdale I wrote about recently in a story called Joseph Grisdale, the Duke of Norfolk and the ‘Majesty of the people’. Joseph was the long-time favourite servant of the 11th Duke of Norfolk, Charles Howard. He was also the nephew of the famous and heroic Hussar Levi Grisdale who I have written much about.

Thomas was born in Arundel in 1808 and like his father went into ‘service’, although Mr Norman of Burnt Ash Farm was nowhere near in the same league as the Duke of Norfolk. He married Ockley-born Charlotte Charman in London in January 1830. Ockley in Surrey was a place where Thomas’s father owned a house. A daughter called Eleanor was born in June, but she died the next year. And then Thomas seems to disappear. Maybe he died soon after witnessing Mr Cocking’s tragic death? I just don’t know.

In 1841 Charlotte was a servant of aristocrat Christopher Thomas Tower at the stately Weald Hall in Brentwood in Essex and she died at her parents’ home of ‘Linacre’ in Cranleigh in Surrey in 1847, aged just thirty-seven.

Weald Hall, Brentwood